READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

Are 1 in 5 Women Really Sexually Assaulted on College Campuses?

If you wanted to know how many young women are sexually assaulted on college campuses, you could easily devise a survey to ask a sample of them directly. But that’s not what advocates of stricter measures to prevent assault tend to do. Instead, they ask ambiguous questions they go on to interpret as suggesting an assault occurred. This almost guarantees wildly inflated numbers.

If you were a university administrator and you wanted to know how prevalent a particular experience was for students on campus, you would probably conduct a survey that asked a few direct questions about that experience—foremost among them the question of whether the student had at some point had the experience you’re interested in. Obvious, right? Recently, we’ve been hearing from many news media sources, and even from President Obama himself, that one in five college women experience sexual assault at some time during their tenure as students. It would be reasonable to assume that the surveys used to arrive at this ratio actually asked the participants directly whether or not they had been assaulted.

But it turns out the web survey that produced the one-in-five figure did no such thing. Instead, it asked students whether they had had any of several categories of experience the study authors later classified as sexual assault, or attempted sexual assault, in their analysis. This raises the important question of how we should define sexual assault when we’re discussing the issue—along with the related question of why we’re not talking about a crime that’s more clearly defined, like rape.

Of course, whatever you call it, sexual violence is such a horrible crime that most of us are willing to forgive anyone who exaggerates the numbers or paints an overly frightening picture of reality in an attempt to prevent future cases. (The issue is so serious that PolitiFact refrained from applying their trademark Truth-O-Meter to the one-in-five figure.)

But there are four problems with this attitude. The first is that for every supposed assault there is an alleged perpetrator. Dramatically overestimating the prevalence of the crime comes with the attendant risk of turning public perception against the accused, making it more difficult for the innocent to convince anyone of their innocence.

The second problem is that by exaggerating the danger in an effort to protect college students we’re sabotaging any opportunity these young adults may have to make informed decisions about the risks they take on. No one wants students to die in car accidents either, but we don’t manipulate the statistics to persuade them one in five drivers will die in a crash before they graduate from college.

The third problem is that going to college and experimenting with sex are for many people a wonderful set of experiences they remember fondly for the rest of their lives. Do we really want young women to barricade themselves in their dorms? Do we want young men to feel like they have to get signed and notarized documentation of consent before they try to kiss anyone? The fourth problem I’ll get to in a bit.

We need to strike some appropriate balance in our efforts to raise awareness without causing paranoia or inspiring unwarranted suspicion. And that balance should be represented by the results of our best good-faith effort to arrive at as precise an understanding of the risk as our most reliable methods allow. For this purpose, The Department of Justice’s Campus Sexual Assault Study, the source of the oft-cited statistic, is all but completely worthless. It has limitations, to begin with, when it comes to representativeness, since it surveyed students on just two university campuses. And, while the overall sample was chosen randomly, the 42% response rate implies a great deal of self-selection on behalf of the participants. The researchers did compare late responders to early ones to see if there was a systematic difference in their responses. But this doesn’t by any means rule out the possibility that many students chose categorically not to respond because they had nothing to say, and therefore had no interest in the study. (Some may have even found it offensive.) These are difficulties common to this sort of simple web-based survey, and they make interpreting the results problematic enough to recommend against their use in informing policy decisions.

The biggest problems with the study, however, are not with the sample but with the methods. The survey questions appear to have been deliberately designed to generate inflated incidence rates. The basic strategy of avoiding direct questions about whether the students had been the victims of sexual assault is often justified with the assumption that many young people can’t be counted on to know what actions constitute rape and assault. But attempting to describe scenarios in survey items to get around this challenge opens the way for multiple interpretations and discounts the role of countless contextual factors. The CSA researchers write, “A surprisingly large number of respondents reported that they were at a party when the incident happened.” Cathy Young, a contributing editor at Reason magazine who analyzed the study all the way back in 2011, wrote that

the vast majority of the incidents it uncovered involved what the study termed “incapacitation” by alcohol (or, rarely, drugs): 14 percent of female respondents reported such an experience while in college, compared to six percent who reported sexual assault by physical force. Yet the question measuring incapacitation was framed ambiguously enough that it could have netted many “gray area” cases: “Has someone had sexual contact with you when you were unable to provide consent or stop what was happening because you were passed out, drugged, drunk, incapacitated, or asleep?” Does “unable to provide consent or stop” refer to actual incapacitation – given as only one option in the question – or impaired judgment? An alleged assailant would be unlikely to get a break by claiming he was unable to stop because he was drunk.

This type of confusion is why it’s important to design survey questions carefully. That the items in the CSA study failed to make the kind of fine distinctions that would allow for more conclusive interpretations suggests the researchers had other goals in mind.

The researchers’ use of the blanket term “sexual assault,” and their grouping of attempted with completed assaults, is equally suspicious. Any survey designer cognizant of all the difficulties of web surveys would likely try to narrow the focus of the study as much as possible, and they would also try to eliminate as many sources of confusion with regard to definitions or descriptions as possible. But, as Young points out,

The CSA Study’s estimate of sexual assault by physical force is somewhat problematic as well – particularly for attempted sexual assaults, which account for nearly two-thirds of the total. Women were asked if anyone had ever had or attempted to have sexual contact with them by using force or threat, defined as “someone holding you down with his or her body weight, pinning your arms, hitting or kicking you, or using or threatening to use a weapon.” Suppose that, during a make-out session, the man tries to initiate sex by rolling on top of the woman, with his weight keeping her from moving away – but once she tells him to stop, he complies. Would this count as attempted sexual assault?

The simplest way to get around many of these difficulties would have been to ask the survey participants directly whether they had experienced the category of crime the researchers were interested in. If the researchers were concerned that the students might not understand that being raped while drunk still counts as rape, why didn’t they just ask the participants a question to that effect? It’s a simple enough question to devise.

The study did pose a follow up question to participants it classified as victims of forcible assault, the responses to which hint at the students’ actual thoughts about the incidents. It turns out 37 percent of so-called forcible assault victims explained that they hadn’t contacted law enforcement because they didn’t think the incident constituted a crime. That bears repeating: a third of the students the study says were forcibly assaulted didn’t think any crime had occurred. With regard to another category of victims, those of incapacitated assault, Young writes, “Not surprisingly, three-quarters of the female students in this category did not label their experience as rape.” Of those the study classified as actually having been raped while intoxicated, only 37 percent believed they had in fact been raped. Two thirds of the women the study labels as incapacitated rape victims didn’t believe they had been raped. Why so much disagreement on such a serious issue? Of the entire incapacitated sexual assault victim category, Young writes,

Two-thirds said they did not report the incident to the authorities because they didn’t think it was serious enough. Interestingly, only two percent reported having suffered emotional or psychological injury – a figure so low that the authors felt compelled to include a footnote asserting that the actual incidence of such trauma was undoubtedly far higher.

So the largest category making up the total one-in-five statistic is predominantly composed of individuals who didn’t think what happened to them was serious enough to report. And nearly all of them came away unscathed, both physically and psychologically.

The impetus behind the CSA study was a common narrative about a so-called “rape culture” in which sexual violence is accepted as normal and young women fail to report incidents because they’re convinced you’re just supposed to tolerate it. That was the researchers’ rationale for using their own classification scheme for the survey participants’ experiences even when it was at odds with the students’ beliefs. But researchers have been doing this same dance for thirty years. As Young writes,

When the first campus rape studies in the 1980s found that many women labeled as victims by researchers did not believe they had been raped, the standard explanation was that cultural attitudes prevent women from recognizing forced sex as rape if the perpetrator is a close acquaintance. This may have been true twenty-five years ago, but it seems far less likely in our era of mandatory date rape and sexual assault workshops and prevention programs on college campuses.

The CSA also surveyed a large number of men, almost none of whom admitted to assaulting women. The researchers hypothesize that the men may have feared the survey wasn’t really anonymous, but that would mean they knew the behaviors in question were wrong. Again, if the researchers are really worried about mistaken beliefs regarding the definition of rape, they could investigate the issue with a few added survey items.

The huge discrepancies between incidences of sexual violence as measured by researchers and as reported by survey participants becomes even more suspicious in light of the history of similar studies. Those campus rape studies Young refers to from the 1980s produced a ratio of one in four. Their credibility was likewise undermined by later surveys that found that most of the supposed victims didn’t believe they’d been raped, and around forty percent of them went on to have sex with their alleged assailants again. A more recent study by the CDC used similar methods—a phone survey with a low response rate—and concluded that one in five women has been raped at some time in her life. Looking closer at this study, feminist critic and critic of feminism Christina Hoff Sommers attributes this finding as well to “a non-representative sample and vaguely worded questions.” It turns out activists have been conducting different versions of this same survey, and getting similarly, wildly inflated results for decades.

Sommers challenges the CDC findings in a video everyone concerned with the issue of sexual violence should watch. We all need to understand that well-intentioned and intelligent people can, and often do, get carried away with activism that seems to have laudable goals but ends up doing more harm than good. Some people even build entire careers on this type of crusading. And PR has become so sophisticated that we never need to let a shortage, or utter lack of evidence keep us from advocating for our favorite causes. But there’s still a fourth problem with crazily exaggerated risk assessments—they obfuscate issues of real importance, making it more difficult to come up with real solutions. As Sommers explains,

To prevent rape and sexual assault we need state-of-the-art research. We need sober estimates. False and sensationalist statistics are going to get in the way of effective policies. And unfortunately, when it comes to research on sexual violence, exaggeration and sensation are not the exception; they are the rule. If you hear about a study that shows epidemic levels of sexual violence against American women, or college students, or women in the military, I can almost guarantee the researchers used some version of the defective CDC methodology. Now by this method, known as advocacy research, you can easily manufacture a women’s crisis. But here’s the bottom line: this is madness. First of all it trivializes the horrific pain and suffering of survivors. And it sends scarce resources in the wrong direction. Sexual violence is too serious a matter for antics, for politically motivated posturing. And right now the media, politicians, rape culture activists—they are deeply invested in these exaggerated numbers.

So while more and more normal, healthy, and consensual sexual practices are considered crimes, actual acts of exploitation and violence are becoming all the more easily overlooked in the atmosphere of paranoia. And college students face the dilemma of either risking assault or accusation by going out to enjoy themselves or succumbing to the hysteria and staying home, missing out on some of the richest experiences college life has to offer.

One in five is a truly horrifying ratio. As conservative crime researcher Heather McDonald points out, “Such an assault rate would represent a crime wave unprecedented in civilized history. By comparison, the 2012 rape rate in New Orleans and its immediately surrounding parishes was .0234 percent; the rate for all violent crimes in New Orleans in 2012 was .48 percent.” I don’t know how a woman can pass a man on a sidewalk after hearing such numbers and not look at him with suspicion. Most of the reforms rape culture activists are pushing for now chip away at due process and strip away the rights of the accused. No one wants to make coming forward any more difficult for actual victims, but our first response to anyone making such a grave accusation—making any accusation—should be skepticism. Victims suffer severe psychological trauma, but then so do the falsely accused. The strongest evidence of an honest accusation is often the fact that the accuser must incur some cost in making it. That’s why we say victims who come forward are heroic. That’s the difference between a victim and a survivor.

Trumpeting crazy numbers creates the illusion that a large percentage of men are monsters, and this fosters an us-versus-them mentality that obliterates any appreciation for the difficulty of establishing guilt. That would be a truly scary world to live in. Fortunately, we in the US don’t really live in such a world. Sex doesn’t have to be that scary. It’s usually pretty damn fun. And the vast majority of men you meet—the vast majority of women as well—are good people. In fact, I’d wager most men would step in if they were around when some psychopath was trying to rape someone.

Also read:

And:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

And:

VIOLENCE IN HUMAN EVOLUTION AND POSTMODERNISM'S CAPTURE OF ANTHROPOLOGY

The Spider-Man Stars' Dust-up over Pseudo-Sexism

You may have noticed that the term sexism has come to refer to any suggestion that there may be meaningful differences between women and men, or between what’s considered feminine and what’s considered masculine. But is the denial of sex differences really what’s best for women? Is it what’s best for anyone.

A new definition of the word sexism has taken hold in the English-speaking world, even to the point where it’s showing up in official definitions. No longer used merely to describe the belief that women are somehow inferior to men, sexism can now refer to any belief in gender differences. Case in point: when Spider-Man star Andrew Garfield fielded a question from a young boy about how the superhero came by his iconic costume by explaining that he sewed it himself, even though sewing is “kind of a feminine thing to do,” Emma Gray and The Huffington Post couldn’t resist griping about Garfield’s “Casual Sexism” and celebrating his girlfriend Emma Stone’s “Most Perfect Way” of calling it out. Gray writes,

Instead of letting the comment—which assumes that there is something fundamentally female about sewing, and that doing such a “girly” thing must be qualified with a “masculine” outcome—slide, Stone turned the Q&A panel into an important teachable moment. She stopped her boyfriend and asked: “It's feminine, how?”

Those three words are underwhelming enough to warrant suspicion that Gray is really just cheerleading for someone she sees as playing for the right team.

A few decades ago, people would express beliefs about the proper roles and places for women quite openly in public. Outside of a few bastions of radical conservatism, you’re unlikely to hear anyone say that women shouldn’t be allowed to run businesses or serve in high office today. But rather than being leveled with decreasing frequency the charge of sexism is now applied to a wider and more questionable assortment of ideas and statements. Surprised at having fallen afoul of this broadening definition of sexism, Garfield responded to Stone’s challenge by saying,

It’s amazing how you took that as an insult. It’s feminine because I would say femininity is about more delicacy and precision and detail work and craftsmanship. Like my mother, she’s an amazing craftsman. She in fact made my first Spider-Man costume when I was three. So I use it as a compliment, to compliment the feminine in women but in men as well. We all have feminine in us, young men.

Gray sees that last statement as a result of how Stone “pressed Garfield to explain himself.” Watch the video, though, and you’ll see she did little pressing. He seemed happy to explain what he meant. And that last line was actually a reiteration of the point he’d made originally by saying, “It’s kind of a feminine thing to do, but he really made a very masculine costume”—the line that Stone pounced on.

Garfield’s handling of both the young boy’s question and Stone’s captious interruption is far more impressive than Stone’s supposedly perfect way of calling him out. Indeed, Stone’s response was crudely ideological, implying quite simply that her boyfriend had revealed something embarrassing about himself—gotcha!—and encouraging him to expound further on his unacceptable ideas so she and the audience could chastise him. She had, like Gray, assumed that any reference to gender roles was sexist by definition. But did Garfield’s original answer to the boy’s question really reveal that he “assumes that there is something fundamentally female about sewing, and that doing such a ‘girly’ thing must be qualified with a ‘masculine’ outcome,” as Gray claims? (Note her deceptively inconsistent use of scare quotes and actual quotes.)

Garfield’s thinking throughout the exchange was quite sophisticated. First, he tried to play up Spider-Man’s initiative and self-sufficiency because he knew the young fan would appreciate these qualities in his hero. Then he seems to have realized that the young boy might be put off by the image of his favorite superhero engaging in an activity that’s predominantly taken up by women. Finally, he realized he could use this potential uneasiness as an opportunity for making the point that just because a male does something generally considered feminine that doesn’t mean he’s any less masculine. This is the opposite of sexism. So why did Stone and Gray cry foul?

One of the tenets of modern feminism is that gender roles are either entirely chimerical or, to the extent that they exist, socially constructed. In other words, they’re nothing but collective delusions. Accepting, acknowledging, or referring to gender roles then, especially in the presence of a young child, abets in the perpetuation of these separate roles. Another tenet of modern feminism that comes into play here is that gender roles are inextricably linked to gender oppression. The only way for us as a society to move toward greater equality, according to this ideology, is for us to do away with gender roles altogether. Thus, when Garfield or anyone else refers to them as if they were real or in any way significant, he must be challenged.

One of the problems with Stone’s and Gray’s charge of sexism is that there happens to be a great deal of truth in every aspect of Garfield’s answer to the boy’s question. Developmental psychologists consistently find that young children really are preoccupied with categorizing behaviors by gender and that the salience of gender to children arises so reliably and at so young an age that it’s unlikely to stem from socialization.

Studies have also consistently found that women tend to excel in tasks requiring fine motor skill, while men excel in most other dimensions of motor ability. And what percentage of men ever go beyond sewing buttons on their shirts—if they do even that? Why but for the sake of political correctness would anyone deny this difference? Garfield’s response to Stone’s challenge was also remarkably subtle. He didn’t act as though he’d been caught in a faux pas but instead turned the challenge around, calling Stone out for assuming he somehow intended to disparage women. He then proudly expounded on his original point. If anything, it looked a little embarrassing for Stone.

Modern feminism has grown over the past decade to include the push for LGBT rights. Historically, gender roles were officially sanctioned and strictly enforced, so it was understandable that anyone advocating for women’s rights would be inclined to question those roles. Today, countless people who don’t fit neatly into conventional gender categories are in a struggle with constituencies who insist their lifestyles and sexual preferences are unnatural. But even those of us who support equal rights for LGBT people have to ask ourselves if the best strategy for combating bigotry is an aggressive and wholesale denial of gender. Isn’t it possible to recognize gender differences, and even celebrate them, without trying to enforce them prescriptively? Can’t we accept the possibility that some average differences are innate without imposing definitions on individuals or punishing them for all the ways they upset expectations? And can’t we challenge religious conservatives for the asinine belief that nature sets up rigid categories and the idiotic assumption that biology is about order as opposed to diversity instead of ignoring (or attacking) psychologists who study gender differences?

I think most people realize there’s something not just unbecoming but unfair about modern feminism’s anti-gender attitude. And most people probably don’t appreciate all the cheap gotchas liberal publications like The Huffington Post and The Guardian and Slate are so fond of touting. Every time feminists accuse someone of sexism for simply referring to obvious gender differences, they belie their own case that feminism is no more and no less than a belief in the equality of women. Only twenty percent of Americans identify themselves as feminists, while over eighty percent believe in equality for women. Feminism, like sexism, has clearly come to mean something other than what it used to. It may be the case that just as the gender roles of the past century gradually came to be seen as too rigid so too that century’s ideologies are increasingly seen as too lacking in nuance and their proponents too quick to condemn. It may even be that we Americans and Brits no longer need churchy ideologies to tell us all people deserve to be treated equally.

Also read:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

And:

And:

WHY I WON'T BE ATTENDING THE GENDER-FLIPPED SHAKESPEARE PLAY

Why I Won't Be Attending the Gender-Flipped Shakespeare Play

Gender-flipped performances are often billed as experiments to help audiences reconsider and look more deeply into what we consider the essential characteristics of males and females. But not to far beneath the surface, you find that they tend to be more like ideological cudgels for those who would deny biological differences.

The Guardian’s “Women’s Blog” reports that “Gender-flips used to challenge sexist stereotypes are having a moment,” and this is largely owing, author Kira Cochrane suggests, to the fact that “Sometimes the best way to make a point about sexism is also the simplest.” This simple approach to making a point consists of taking a work of art or piece of advertising and swapping the genders featured in them. Cochrane goes on to point out that “the gender-flip certainly isn’t a new way to make a political point,” and notes that “it’s with the recent rise of feminist campaigning and online debate that this approach has gone mainstream.”

What is the political point gender-flips are making? As a dancer in a Jennifer Lopez video that reverses the conventional gender roles asks, “Why do men always objectify the women in every single video?” Australian comedian Christiaan Van Vuuren explains that he posed for a reproduction of a GQ cover originally featuring a sexy woman to call attention to the “over-sexualization of the female body in the high-fashion world.” The original cover photo of Miranda Kerr is undeniably beautiful. The gender-flipped version is funny. The obvious takeaway is that we look at women and men differently (gasp!). When women strike an alluring pose, or don revealing clothes, it’s sexy. When men try to do the same thing, it’s ridiculous. Feminists insist that this objectification or over-sexualization of women is a means of oppression. But is it? And are gender-flips simple ways of making a point, or just cheap gimmicks?

Tonight, my alma mater IPFW is hosting a production called “Juliet and Romeo,” a gender-flipped version of Shakespeare’s most recognizable play. The lead on the Facebook page for the event asks us to imagine that “Juliet is instead a bold Montague who courts a young, sheltered Capulet by the name of Romeo.” Lest you fear the production is just a stunt to make a political point about gender, the hosts have planned a “panel discussion focusing on Shakespeare, gender, and language.” Many former classmates and teachers, most of whom I consider friends, a couple I consider good friends, are either attending or participating in the event. But I won’t be going.

I don’t believe the production is being put on in the spirit of open-minded experimentation. Like the other gender-flip examples, the purpose of staging “Juliet and Romeo” is to make a point about stereotypes. And I believe this proclivity toward using literature as fodder to fuel ideological agendas is precisely what’s most wrong with English lit programs in today’s universities. There have to be better ways to foster interest in great works than by letting activists posing as educators use them as anvils to hammer agendas into students’ heads against.

You may take the position that my objections would carry more weight were I to attend the event before rendering judgment on it. But I believe the way to approach literature is as an experience, not as a static set of principles or stand-alone abstractions. And I don’t want thoughts about gender politics to intrude on my experience of Shakespeare—especially when those thoughts are of such dubious merit. I want to avoid the experience of a gender-flipped production of Shakespeare because I believe scholarship should push us farther into literature—enhance our experience of it, make it more immediate and real—not cast us out of it by importing elements of political agendas and making us cogitate about some supposed implications for society of what’s going on before our eyes.

Regarding that political point, I see no contradiction in accepting, even celebrating, our culture’s gender roles while at the same time supporting equal rights for both genders. Sexism is a belief that one gender is inferior to the other. Demonstrating that people of different genders tend to play different roles in no way proves that either is being treated as inferior. As for objectification and over-sexualization, a moment’s reflection ought to make clear that the feminists are getting this issue perfectly backward. Physical attractiveness is one of the avenues through which women exercise power over men. Miranda Kerr got paid handsomely for that GQ cover. And what could be more arrantly hypocritical than Jennifer Lopez complaining about objectification in music videos? She owes her celebrity in large part to her willingness to allow herself to be objectified. The very concept of objectification is only something we accept from long familiarity--people are sexually aroused by other people, not objects.

I’m not opposed to having a discussion about gender roles and power relations, but if you have something to say, then say it. I’m not even completely opposed to discussing gender in the context of Shakespeare’s plays. What I am opposed to is people hijacking our experience of Shakespeare to get some message across, people toeing the line by teaching that literature is properly understood by “looking at it through the lens” of one or another well-intentioned but completely unsupported ideology, and people misguidedly making sex fraught and uncomfortable for everyone. I doubt I’m alone in turning to literature, at least in part, to get away from that sort of puritanism in church. Guilt-tripping guys and encouraging women to walk around with a chip on their shoulders must be one of the least effective ways to get people to respect each other more we've ever come up with.

But, when you guys do a performance of the original Shakespeare, you can count on me being there to experience it.

Update:

The link to this post on Facebook generated some heated commentary. Some were denials of ideological intentions on behalf of those putting on the event. Some were mischaracterizations based on presumed “traditionalist” associations with my position. Some made the point that Shakespeare himself played around with gender, so it should be okay for others to do the same with his work. In the end, I did feel compelled to attend the event because I had taken such a strong position.

Having flipflopped and attended the event, I have to admit I enjoyed it. All the people involved were witty, charming, intellectually stimulating, and pretty much all-around delightful.

But, as was my original complaint, it was quite clear—and at two points explicitly stated—that the "experiment" entailed using the play as a springboard for a discussion of current issues like marriage rights. Everyone, from the cast to audience members, was quick to insist after the play that they felt it was completely natural and convincing. But gradually more examples of "awkward," "uncomfortable," or "weird" lines or scenes came up. Shannon Bischoff, a linguist one commenter characterized as the least politically correct guy I’d ever meet, did in fact bring up a couple aspects of the adaptation that he found troubling. But even he paused after saying something felt weird, as if to say, "Is that alright?" (Being weirded out about a 15 year old Romeo being pursued by a Juliet in her late teens was okay because it was about age not gender.)

The adapter himself, Jack Cant, said at one point that though he was tempted to rewrite some of the parts that seemed really strange he decided to leave them in because he wanted to let people be uncomfortable. The underlying assumption of the entire discussion was that gender is a "social construct" and that our expectations are owing solely to "stereotypes." And the purpose of the exercise was for everyone to be brought face-to-face with their assumptions about gender so that they could expiate them. I don't think any fair-minded attendee could deny the agreed-upon message was that this is a way to help us do away with gender roles—and that doing so would be a good thing. (If there was any doubt, Jack’s wife eliminated it when she stood up from her seat in the audience to say she wondered if Jack had learned enough from the exercise to avoid applying gender stereotypes to his nieces.) And this is exactly what I mean by ideology. Sure, Shakespeare played around with gender in As You Like It and Twelfth Night. But he did it for dramatic or comedic effect primarily, and to send a message secondarily—or more likely not at all.

For the record, I think biology plays a large (but of course not exclusive) part in gender roles, I enjoy and celebrate gender roles (love being a man; love women who love being women), but I also support marriage rights for homosexuals and try to be as accepting as I can of people who don't fit the conventional roles.

To make one further clarification: whether you support an anti-gender agenda and whether you think Shakespeare should be used as a tool for this or any other ideological agenda are two separate issues. I happen not to support anti-genderism. My main point in this post, however, is that ideology—good, bad, valid, invalid—should not play a part in literature education. Because, for instance, while students are being made to feel uncomfortable about their unexamined gender assumptions, they're not feeling uncomfortable about, say, whether Romeo might be rushing into marriage too hastily, or whether Juliet will wake up in time to keep him from drinking the poison—you know, the actual play.

Whether Shakespeare was sending a message or not, I'm sure he wanted first and foremost for his audiences to respond to the characters he actually created. And we shouldn't be using "lenses" to look at plays; we should be experiencing them. They're not treatises. They're not coded allegories. And, as old as they may be to us, every generation of students gets to discover them anew.

We can discuss politics and gender or whatever you want. There's a time and a place for that and it's not in a lit classroom. Sure, let's encourage students to have open minds about gender and other issues, and let's help them to explore their culture and their own habits of thought. There are good ways to do that—ideologically adulterated Shakespeare is not one of them.

Also read:

FROM DARWIN TO DR. SEUSS: DOUBLING DOWN ON THE DUMBEST APPROACH TO COMBATTING RACISM

And:

HOW TO GET KIDS TO READ LITERATURE WITHOUT MAKING THEM HATE IT

And:

THE ISSUE WITH JURASSIC WORLD NO ONE HAS THE BALLS TO TALK ABOUT

The Self-Righteousness Instinct: Steven Pinker on the Better Angels of Modernity and the Evils of Morality

Is violence really declining? How can that be true? What could be causing it? Why are so many of us convinced the world is going to hell in a hand basket? Steven Pinker attempts to answer these questions in his magnificent and mind-blowing book.

Steven Pinker is one of the few scientists who can write a really long book and still expect a significant number of people to read it. But I have a feeling many who might be vaguely intrigued by the buzz surrounding his 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined wonder why he had to make it nearly seven hundred outsized pages long. Many curious folk likely also wonder why a linguist who proselytizes for psychological theories derived from evolutionary or Darwinian accounts of human nature would write a doorstop drawing on historical and cultural data to describe the downward trajectories of rates of the worst societal woes. The message that violence of pretty much every variety is at unprecedentedly low rates comes as quite a shock, as it runs counter to our intuitive, news-fueled sense of being on a crash course for Armageddon. So part of the reason behind the book’s heft is that Pinker has to bolster his case with lots of evidence to get us to rethink our views. But flipping through the book you find that somewhere between half and a third of its mass is devoted, not to evidence of the decline, but to answering the questions of why the trend has occurred and why it gives every indication of continuing into the foreseeable future. So is this a book about how evolution has made us violent or about how culture is making us peaceful?

The first thing that needs to be said about Better Angels is that you should read it. Despite its girth, it’s at no point the least bit cumbersome to read, and at many points it’s so fascinating that, weighty as it is, you’ll have a hard time putting it down. Pinker has mastered a prose style that’s simple and direct to the point of feeling casual without ever wanting for sophistication. You can also rest assured that what you’re reading is timely and important because it explores aspects of history and social evolution that impact pretty much everyone in the world but that have gone ignored—if not censoriously denied—by most of the eminences contributing to the zeitgeist since the decades following the last world war.

Still, I suspect many people who take the plunge into the first hundred or so pages are going to feel a bit disoriented as they try to figure out what the real purpose of the book is, and this may cause them to falter in their resolve to finish reading. The problem is that the resistance Better Angels runs to such a prodigious page-count simultaneously anticipating and responding to doesn’t come from news media or the blinkered celebrities in the carnivals of sanctimonious imbecility that are political talk shows. It comes from Pinker’s fellow academics. The overall point of Better Angels remains obscure owing to some deliberate caginess on the author’s part when it comes to identifying the true targets of his arguments.

This evasiveness doesn’t make the book difficult to read, but a quality of diffuseness to the theoretical sections, a multitude of strands left dangling, does at points make you doubt whether Pinker had a clear purpose in writing, which makes you doubt your own purpose in reading. With just a little tying together of those strands, however, you start to see that while on the surface he’s merely righting the misperception that over the course of history our species has been either consistently or increasingly violent, what he’s really after is something different, something bigger. He’s trying to instigate, or at least play a part in instigating, a revolution—or more precisely a renaissance—in the way scholars and intellectuals think not just about human nature but about the most promising ways to improve the lot of human societies.

The longstanding complaint about evolutionary explanations of human behavior is that by focusing on our biology as opposed to our supposedly limitless capacity for learning they imply a certain level of fixity to our nature, and this fixedness is thought to further imply a limit to what political reforms can accomplish. The reasoning goes, if the explanation for the way things are is to be found in our biology, then, unless our biology changes, the way things are is the way they’re going to remain. Since biological change occurs at the glacial pace of natural selection, we’re pretty much stuck with the nature we have.

Historically, many scholars have made matters worse for evolutionary scientists today by applying ostensibly Darwinian reasoning to what seemed at the time obvious biological differences between human races in intelligence and capacity for acquiring the more civilized graces, making no secret of their conviction that the differences justified colonial expansion and other forms of oppressive rule. As a result, evolutionary psychologists of the past couple of decades have routinely had to defend themselves against charges that they’re secretly trying to advance some reactionary (or even genocidal) agenda. Considering Pinker’s choice of topic in Better Angels in light of this type of criticism, we can start to get a sense of what he’s up to—and why his efforts are discombobulating.

If you’ve spent any time on a university campus in the past forty years, particularly if it was in a department of the humanities, then you have been inculcated with an ideology that was once labeled postmodernism but that eventually became so entrenched in academia, and in intellectual culture more broadly, that it no longer requires a label. (If you took a class with the word "studies" in the title, then you got a direct shot to the brain.) Many younger scholars actually deny any espousal of it—“I’m not a pomo!”—with reference to a passé version marked by nonsensical tangles of meaningless jargon and the conviction that knowledge of the real world is impossible because “the real world” is merely a collective delusion or social construction put in place to perpetuate societal power structures. The disavowals notwithstanding, the essence of the ideology persists in an inescapable but unremarked obsession with those same power structures—the binaries of men and women, whites and blacks, rich and poor, the West and the rest—and the abiding assumption that texts and other forms of media must be assessed not just according to their truth content, aesthetic virtue, or entertainment value, but also with regard to what we imagine to be their political implications. Indeed, those imagined political implications are often taken as clear indicators of the author’s true purpose in writing, which we must sniff out—through a process called “deconstruction,” or its anemic offspring “rhetorical analysis”—lest we complacently succumb to the subtle persuasion.

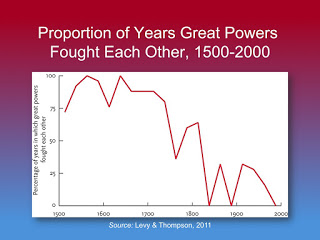

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, faith in what we now call modernism inspired intellectuals to assume that the civilizations of Western Europe and the United States were on a steady march of progress toward improved lives for all their own inhabitants as well as the world beyond their borders. Democracy had brought about a new age of government in which rulers respected the rights and freedom of citizens. Medicine was helping ever more people live ever longer lives. And machines were transforming everything from how people labored to how they communicated with friends and loved ones. Everyone recognized that the driving force behind this progress was the juggernaut of scientific discovery. But jump ahead a hundred years to the early twenty-first century and you see a quite different attitude toward modernity. As Pinker explains in the closing chapter of Better Angels,

A loathing of modernity is one of the great constants of contemporary social criticism. Whether the nostalgia is for small-town intimacy, ecological sustainability, communitarian solidarity, family values, religious faith, primitive communism, or harmony with the rhythms of nature, everyone longs to turn back the clock. What has technology given us, they say, but alienation, despoliation, social pathology, the loss of meaning, and a consumer culture that is destroying the planet to give us McMansions, SUVs, and reality television? (692)

The social pathology here consists of all the inequities and injustices suffered by the people on the losing side of those binaries all us closet pomos go about obsessing over. Then of course there’s industrial-scale war and all the other types of modern violence. With terrorism, the War on Terror, the civil war in Syria, the Israel-Palestine conflict, genocides in the Sudan, Kosovo, and Rwanda, and the marauding bands of drugged-out gang rapists in the Congo, it seems safe to assume that science and democracy and capitalism have contributed to the construction of an unsafe global system with some fatal, even catastrophic design flaws. And that’s before we consider the two world wars and the Holocaust. So where the hell is this decline Pinker refers to in his title?

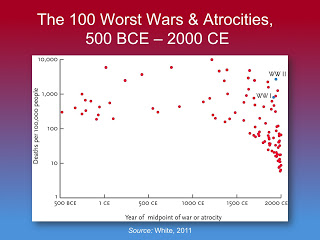

One way to think about the strain of postmodernism or anti-modernism with the most currency today (and if you’re reading this essay you can just assume your views have been influenced by it) is that it places morality and politics—identity politics in particular—atop a hierarchy of guiding standards above science and individual rights. So, for instance, concerns over the possibility that a negative image of Amazonian tribespeople might encourage their further exploitation trump objective reporting on their culture by anthropologists, even though there’s no evidence to support those concerns. And evidence that the disproportionate number of men in STEM fields reflects average differences between men and women in lifestyle preferences and career interests is ignored out of deference to a political ideal of perfect parity. The urge to grant moral and political ideals veto power over science is justified in part by all the oppression and injustice that abounds in modern civilizations—sexism, racism, economic exploitation—but most of all it’s rationalized with reference to the violence thought to follow in the wake of any movement toward modernity. Pinker writes,

“The twentieth century was the bloodiest in history” is a cliché that has been used to indict a vast range of demons, including atheism, Darwin, government, science, capitalism, communism, the ideal of progress, and the male gender. But is it true? The claim is rarely backed up by numbers from any century other than the 20th, or by any mention of the hemoclysms of centuries past. (193)

He gives the question even more gravity when he reports that all those other areas in which modernity is alleged to be such a colossal failure tend to improve in the absence of violence. “Across time and space,” he writes in the preface, “the more peaceable societies also tend to be richer, healthier, better educated, better governed, more respectful of their women, and more likely to engage in trade” (xxiii). So the question isn’t just about what the story with violence is; it’s about whether science, liberal democracy, and capitalism are the disastrous blunders we’ve learned to think of them as or whether they still just might hold some promise for a better world.

*******

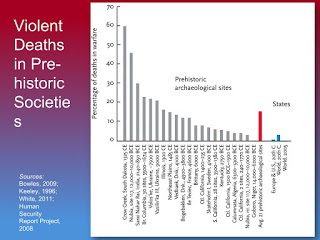

It’s in about the third chapter of Better Angels that you start to get the sense that Pinker’s style of thinking is, well, way out of style. He seems to be marching to the beat not of his own drummer but of some drummer from the nineteenth century. In the chapter previous, he drew a line connecting the violence of chimpanzees to that in what he calls non-state societies, and the images he’s left you with are savage indeed. Now he’s bringing in the philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s idea of a government Leviathan that once established immediately works to curb the violence that characterizes us humans in states of nature and anarchy. According to sociologist Norbert Elias’s 1969 book, The Civilizing Process, a work whose thesis plays a starring role throughout Better Angels, the consolidation of a Leviathan in England set in motion a trend toward pacification, beginning with the aristocracy no less, before spreading down to the lower ranks and radiating out to the countries of continental Europe and onward thence to other parts of the world. You can measure your feelings of unease in response to Pinker’s civilizing scenario as a proxy for how thoroughly steeped you are in postmodernism.

The two factors missing from his account of the civilizing pacification of Europe that distinguish it from the self-congratulatory and self-exculpatory sagas of centuries past are the innate superiority of the paler stock and the special mission of conquest and conversion commissioned by a Christian god. In a later chapter, Pinker violates the contemporary taboo against discussing—or even thinking about—the potential role of average group (racial) differences in a propensity toward violence, but he concludes the case for any such differences is unconvincing: “while recent biological evolution may, in theory, have tweaked our inclinations toward violence and nonviolence, we have no good evidence that it actually has” (621). The conclusion that the Civilizing Process can’t be contingent on congenital characteristics follows from the observation of how readily individuals from far-flung regions acquire local habits of self-restraint and fellow-feeling when they’re raised in modernized societies. As for religion, Pinker includes it in a category of factors that are “Important but Inconsistent” with regard to the trend toward peace, dismissing the idea that atheism leads to genocide by pointing out that “Fascism happily coexisted with Catholicism in Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Croatia, and though Hitler had little use for Christianity, he was by no means an atheist, and professed that he was carrying out a divine plan.” Though he cites several examples of atrocities incited by religious fervor, he does credit “particular religious movements at particular times in history” with successfully working against violence (677).

Despite his penchant for blithely trampling on the taboos of the liberal intelligentsia, Pinker refuses to cooperate with our reflex to pigeonhole him with imperialists or far-right traditionalists past or present. He continually holds up to ridicule the idea that violence has any redeeming effects. In a section on the connection between increasing peacefulness and rising intelligence, he suggests that our violence-tolerant “recent ancestors” can rightly be considered “morally retarded” (658).

He singles out George W. Bush as an unfortunate and contemptible counterexample in a trend toward more complex political rhetoric among our leaders. And if it’s either gender that comes out not looking as virtuous in Better Angels it ain’t the distaff one. Pinker is difficult to categorize politically because he’s a scientist through and through. What he’s after are reasoned arguments supported by properly weighed evidence.

But there is something going on in Better Angels beyond a mere accounting for the ongoing decline in violence that most of us are completely oblivious of being the beneficiaries of. For one, there’s a challenge to the taboo status of topics like genetic differences between groups, or differences between individuals in IQ, or differences between genders. And there’s an implicit challenge as well to the complementary premises he took on more directly in his earlier book The Blank Slate that biological theories of human nature always lead to oppressive politics and that theories of the infinite malleability of human behavior always lead to progress (communism relies on a blank slate theory, and it inspired guys like Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot to murder untold millions). But the most interesting and important task Pinker has set for himself with Better Angels is a restoration of the Enlightenment, with its twin pillars of science and individual rights, to its rightful place atop the hierarchy of our most cherished guiding principles, the position we as a society misguidedly allowed to be usurped by postmodernism, with its own dual pillars of relativism and identity politics.

But, while the book succeeds handily in undermining the moral case against modernism, it does so largely by stealth, with only a few explicit references to the ideologies whose advocates have dogged Pinker and his fellow evolutionary psychologists for decades. Instead, he explores how our moral intuitions and political ideals often inspire us to make profoundly irrational arguments for positions that rational scrutiny reveals to be quite immoral, even murderous. As one illustration of how good causes can be taken to silly, but as yet harmless, extremes, he gives the example of how “violence against children has been defined down to dodgeball” (415) in gym classes all over the US, writing that

The prohibition against dodgeball represents the overshooting of yet another successful campaign against violence, the century-long movement to prevent the abuse and neglect of children. It reminds us of how a civilizing offensive can leave a culture with a legacy of puzzling customs, peccadilloes, and taboos. The code of etiquette bequeathed to us by this and other Rights Revolutions is pervasive enough to have acquired a name. We call it political correctness. (381)

Such “civilizing offensives” are deliberately undertaken counterparts to the fortuitously occurring Civilizing Process Elias proposed to explain the jagged downward slope in graphs of relative rates of violence beginning in the Middle Ages in Europe. The original change Elias describes came about as a result of rulers consolidating their territories and acquiring greater authority. As Pinker explains,

Once Leviathan was in charge, the rules of the game changed. A man’s ticket to fortune was no longer being the baddest knight in the area but making a pilgrimage to the king’s court and currying favor with him and his entourage. The court, basically a government bureaucracy, had no use for hotheads and loose cannons, but sought responsible custodians to run its provinces. The nobles had to change their marketing. They had to cultivate their manners, so as not to offend the king’s minions, and their empathy, to understand what they wanted. The manners appropriate for the court came to be called “courtly” manners or “courtesy.” (75)

And this higher premium on manners and self-presentation among the nobles would lead to a cascade of societal changes.

Elias first lighted on his theory of the Civilizing Process as he was reading some of the etiquette guides which survived from that era. It’s striking to us moderns to see that knights of yore had to be told not to dispose of their snot by shooting it into their host’s table cloth, but that simply shows how thoroughly people today internalize these rules. As Elias explains, they’ve become second nature to us. Of course, we still have to learn them as children. Pinker prefaces his discussion of Elias’s theory with a recollection of his bafflement at why it was so important for him as a child to abstain from using his knife as a backstop to help him scoop food off his plate with a fork. Table manners, he concludes, reside on the far end of a continuum of self-restraint at the opposite end of which are once-common practices like cutting off the nose of a dining partner who insults you. Likewise, protecting children from the perils of flying rubber balls is the product of a campaign against the once-common custom of brutalizing them. The centrality of self-control is the common underlying theme: we control our urge to misuse utensils, including their use in attacking our fellow diners, and we control our urge to throw things at our classmates, even if it’s just in sport. The effect of the Civilizing Process in the Middle Ages, Pinker explains, was that “A culture of honor—the readiness to take revenge—gave way to a culture of dignity—the readiness to control one’s emotions” (72). In other words, diplomacy became more important than deterrence.

What we’re learning here is that even an evolved mind can adjust to changing incentive schemes. Chimpanzees have to control their impulses toward aggression, sexual indulgence, and food consumption in order to survive in hierarchical bands with other chimps, many of whom are bigger, stronger, and better-connected. Much of the violence in chimp populations takes the form of adult males vying for positions in the hierarchy so they can enjoy the perquisites males of lower status must forgo to avoid being brutalized. Lower ranking males meanwhile bide their time, hopefully forestalling their gratification until such time as they grow stronger or the alpha grows weaker. In humans, the capacity for impulse-control and the habit of delaying gratification are even more important because we live in even more complex societies. Those capacities can either lie dormant or they can be developed to their full potential depending on exactly how complex the society is in which we come of age. Elias noticed a connection between the move toward more structured bureaucracies, less violence, and an increasing focus on etiquette, and he concluded that self-restraint in the form of adhering to strict codes of comportment was both an advertisement of, and a type of training for, the impulse-control that would make someone a successful bureaucrat.

Aside from children who can’t fathom why we’d futz with our forks trying to capture recalcitrant peas, we normally take our society’s rules of etiquette for granted, no matter how inconvenient or illogical they are, seldom thinking twice before drawing unflattering conclusions about people who don’t bother adhering to them, the ones for whom they aren’t second nature. And the importance we place on etiquette goes beyond table manners. We judge people according to the discretion with which they dispose of any and all varieties of bodily effluent, as well as the delicacy with which they discuss topics sexual or otherwise basely instinctual.

Elias and Pinker’s theory is that, while the particular rules are largely arbitrary, the underlying principle of transcending our animal nature through the application of will, motivated by an appreciation of social convention and the sensibilities of fellow community members, is what marked the transition of certain constituencies of our species from a violent non-state existence to a relatively peaceful, civilized lifestyle. To Pinker, the uptick in violence that ensued once the counterculture of the 1960s came into full blossom was no coincidence. The squares may not have been as exciting as the rock stars who sang their anthems to hedonism and the liberating thrill of sticking it to the man. But a society of squares has certain advantages—a lower probability for each of its citizens of getting beaten or killed foremost among them.

The Civilizing Process as Elias and Pinker, along with Immanuel Kant, understand it picks up momentum as levels of peace conducive to increasingly complex forms of trade are achieved. To understand why the move toward markets or “gentle commerce” would lead to decreasing violence, us pomos have to swallow—at least momentarily—our animus for Wall Street and all the corporate fat cats in the top one percent of the wealth distribution. The basic dynamic underlying trade is that one person has access to more of something than they need, but less of something else, while another person has the opposite balance, so a trade benefits them both. It’s a win-win, or a positive-sum game. The hard part for educated liberals is to appreciate that economies work to increase the total wealth; there isn’t a set quantity everyone has to divvy up in a zero-sum game, an exchange in which every gain for one is a loss for another. And Pinker points to another benefit:

Positive-sum games also change the incentives for violence. If you’re trading favors or surpluses with someone, your trading partner suddenly becomes more valuable to you alive than dead. You have an incentive, moreover, to anticipate what he wants, the better to supply it to him in exchange for what you want. Though many intellectuals, following in the footsteps of Saints Augustine and Jerome, hold businesspeople in contempt for their selfishness and greed, in fact a free market puts a premium on empathy. (77)

The Occupy Wall Street crowd will want to jump in here with a lengthy list of examples of businesspeople being unempathetic in the extreme. But Pinker isn’t saying commerce always forces people to be altruistic; it merely encourages them to exercise their capacity for perspective-taking. Discussing the emergence of markets, he writes,

The advances encouraged the division of labor, increased surpluses, and lubricated the machinery of exchange. Life presented people with more positive-sum games and reduced the attractiveness of zero-sum plunder. To take advantage of the opportunities, people had to plan for the future, control their impulses, take other people’s perspectives, and exercise the other social and cognitive skills needed to prosper in social networks. (77)

And these changes, the theory suggests, will tend to make merchants less likely on average to harm anyone. As bad as bankers can be, they’re not out sacking villages.

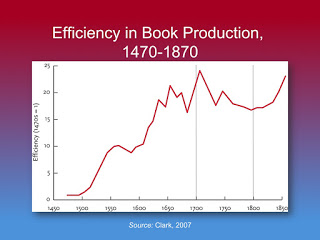

Once you have commerce, you also have a need to start keeping records. And once you start dealing with distant partners it helps to have a mode of communication that travels. As writing moved out of the monasteries, and as technological advances in transportation brought more of the world within reach, ideas and innovations collided to inspire sequential breakthroughs and discoveries. Every advance could be preserved, dispersed, and ratcheted up. Pinker focuses on two relatively brief historical periods that witnessed revolutions in the way we think about violence, and both came in the wake of major advances in the technologies involved in transportation and communication. The first is the Humanitarian Revolution that occurred in the second half of the eighteenth century, and the second covers the Rights Revolutions in the second half of the twentieth. The Civilizing Process and gentle commerce weren’t sufficient to end age-old institutions like slavery and the torture of heretics. But then came the rise of the novel as a form of mass entertainment, and with all the training in perspective-taking readers were undergoing the hitherto unimagined suffering of slaves, criminals, and swarthy foreigners became intolerably imaginable. People began to agitate and change ensued.

The Humanitarian Revolution occurred at the tail end of the Age of Reason and is recognized today as part of the period known as the Enlightenment. According to some scholarly scenarios, the Enlightenment, for all its successes like the American Constitution and the abolition of slavery, paved the way for all those allegedly unprecedented horrors in the first half of the twentieth century. Notwithstanding all this ivory tower traducing, the Enlightenment emerged from dormancy after the Second World War and gradually gained momentum, delivering us into a period Pinker calls the New Peace. Just as the original Enlightenment was preceded by increasing cosmopolitanism, improving transportation, and an explosion of literacy, the transformations that brought about the New Peace followed a burst of technological innovation. For Pinker, this is no coincidence. He writes,

If I were to put my money on the single most important exogenous cause of the Rights Revolutions, it would be the technologies that made ideas and people increasingly mobile. The decades of the Rights Revolutions were the decades of the electronics revolutions: television, transistor radios, cable, satellite, long-distance telephones, photocopiers, fax machines, the Internet, cell phones, text messaging, Web video. They were the decades of the interstate highway, high-speed rail, and the jet airplane. They were the decades of the unprecedented growth in higher education and in the endless frontier of scientific research. Less well known is that they were also the decades of an explosion in book publishing. From 1960 to 2000, the annual number of books published in the United States increased almost fivefold. (477)

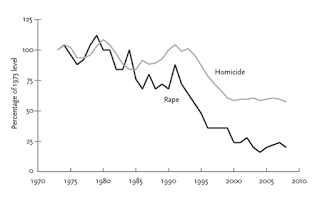

Violence got slightly worse in the 60s. But the Civil Rights Movement was underway, Women’s Rights were being extended into new territories, and people even began to acknowledge that animals could suffer, prompting them to argue that we shouldn’t cause them to do so without cause. Today the push for Gay Rights continues. By 1990, the uptick in violence was over, and so far the move toward peace is looking like an ever greater success. Ironically, though, all the new types of media bringing images from all over the globe into our living rooms and pockets contributes to the sense that violence is worse than ever.

*******

Three factors brought about a reduction in violence over the course of history then: strong government, trade, and communications technology. These factors had the impact they did because they interacted with two of our innate propensities, impulse-control and perspective-taking, by giving individuals both the motivation and the wherewithal to develop them both to ever greater degrees. It’s difficult to draw a clear delineation between developments that were driven by chance or coincidence and those driven by deliberate efforts to transform societies. But Pinker does credit political movements based on moral principles with having played key roles:

Insofar as violence is immoral, the Rights Revolutions show that a moral way of life often requires a decisive rejection of instinct, culture, religion, and standard practice. In their place is an ethics that is inspired by empathy and reason and stated in the language of rights. We force ourselves into the shoes (or paws) of other sentient beings and consider their interests, starting with their interest in not being hurt or killed, and we ignore superficialities that may catch our eye such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and to some extent, species. (475)

Some of the instincts we must reject in order to bring about peace, however, are actually moral instincts.

Pinker is setting up a distinction here between different kinds of morality. The one he describes that’s based on perspective-taking—which evidence he presents later suggests inspires sympathy—and is “stated in the language of rights” is the one he credits with transforming the world for the better. Of the idea that superficial differences shouldn’t distract us from our common humanity, he writes,

This conclusion, of course, is the moral vision of the Enlightenment and the strands of humanism and liberalism that have grown out of it. The Rights Revolutions are liberal revolutions. Each has been associated with liberal movements, and each is currently distributed along a gradient that runs, more or less, from Western Europe to the blue American states to the red American states to the democracies of Latin America and Asia and then to the more authoritarian countries, with Africa and most of the Islamic world pulling up the rear. In every case, the movements have left Western cultures with excesses of propriety and taboo that are deservedly ridiculed as political correctness. But the numbers show that the movements have reduced many causes of death and suffering and have made the culture increasingly intolerant of violence in any form. (475-6)

So you’re not allowed to play dodgeball at school or tell off-color jokes at work, but that’s a small price to pay. The most remarkable part of this passage though is that gradient he describes; it suggests the most violent regions of the globe are also the ones where people are the most obsessed with morality, with things like Sharia and so-called family values. It also suggests that academic complaints about the evils of Western culture are unfounded and startlingly misguided. As Pinker casually points out in his section on Women’s Rights, “Though the United States and other Western nations are often accused of being misogynistic patriarchies, the rest of the world is immensely worse” (413).

The Better Angels of Our Nature came out about a year before Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind, but Pinker’s book beats Haidt’s to the punch by identifying a serious flaw in his reasoning. The Righteous Mind explores how liberals and conservatives conceive of morality differently, and Haidt argues that each conception is equally valid so we should simply work to understand and appreciate opposing political views. It’s not like you’re going to change anyone’s mind anyway, right? But the liberal ideal of resisting certain moral intuitions tends to bring about a rather important change wherever it’s allowed to be realized. Pinker writes that

right or wrong, retracting the moral sense from its traditional spheres of community, authority, and purity entails a reduction of violence. And that retraction is precisely the agenda of classical liberalism: a freedom of individuals from tribal and authoritarian force, and a tolerance of personal choices as long as they do not infringe on the autonomy and well-being of others. (637)

Classical liberalism—which Pinker distinguishes from contemporary political liberalism—can even be viewed as an effort to move morality away from the realm of instincts and intuitions into the more abstract domains of law and reason. The perspective-taking at the heart of Enlightenment morality can be said to consist of abstracting yourself from your identifying characteristics and immediate circumstances to imagine being someone else in unfamiliar straits. A man with a job imagines being a woman who can’t get one. A white man on good terms with law enforcement imagines being a black man who gets harassed. This practice of abstracting experiences and distilling individual concerns down to universal principles is the common thread connecting Enlightenment morality to science.

So it’s probably no coincidence, Pinker argues, that as we’ve gotten more peaceful, people in Europe and the US have been getting better at abstract reasoning as well, a trend which has been going on for as long as researchers have had tests to measure it. Psychologists over the course of the twentieth century have had to adjust IQ test results (the average is always 100) a few points every generation because scores on a few subsets of questions have kept going up. The regular rising of scores is known as the Flynn Effect, after psychologist James Flynn, who was one of the first researchers to realize the trend was more than methodological noise. Having posited a possible connection between scientific and moral reasoning, Pinker asks, “Could there be a moral Flynn Effect?” He explains,

We have several grounds for supposing that enhanced powers of reason—specifically, the ability to set aside immediate experience, detach oneself from a parochial vantage point, and frame one’s ideas in abstract, universal terms—would lead to better moral commitments, including an avoidance of violence. And we have just seen that over the course of the 20th century, people’s reasoning abilities—particularly their ability to set aside immediate experience, detach themselves from a parochial vantage point, and think in abstract terms—were steadily enhanced. (656)

Pinker cites evidence from an array of studies showing that high-IQ people tend have high moral IQs as well. One of them, an infamous study by psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa based on data from over twenty thousand young adults in the US, demonstrates that exceptionally intelligent people tend to hold a particular set of political views. And just as Pinker finds it necessary to distinguish between two different types of morality he suggests we also need to distinguish between two different types of liberalism:

Intelligence is expected to correlate with classical liberalism because classical liberalism is itself a consequence of the interchangeability of perspectives that is inherent to reason itself. Intelligence need not correlate with other ideologies that get lumped into contemporary left-of-center political coalitions, such as populism, socialism, political correctness, identity politics, and the Green movement. Indeed, classical liberalism is sometimes congenial to the libertarian and anti-political-correctness factions in today’s right-of-center coalitions. (662)

And Kanazawa’s findings bear this out. It’s not liberalism in general that increases steadily with intelligence, but a particular kind of liberalism, the type focusing more on fairness than on ideology.

*******

Following the chapters devoted to historical change, from the early Middle Ages to the ongoing Rights Revolutions, Pinker includes two chapters on psychology, the first on our “Inner Demons” and the second on our “Better Angels.” Ideology gets some prime real estate in the Demons chapter, because, he writes, “the really big body counts in history pile up” when people believe they’re serving some greater good. “Yet for all that idealism,” he explains, “it’s ideology that drove many of the worst things that people have ever done to each other.” Christianity, Nazism, communism—they all “render opponents of the ideology infinitely evil and hence deserving of infinite punishment” (556). Pinker’s discussion of morality, on the other hand, is more complicated. It begins, oddly enough, in the Demons chapter, but stretches into the Angels one as well. This is how the section on morality in the Angels chapter begins:

The world has far too much morality. If you added up all the homicides committed in pursuit of self-help justice, the casualties of religious and revolutionary wars, the people executed for victimless crimes and misdemeanors, and the targets of ideological genocides, they would surely outnumber the fatalities from amoral predation and conquest. The human moral sense can excuse any atrocity in the minds of those who commit it, and it furnishes them with motives for acts of violence that bring them no tangible benefit. The torture of heretics and conversos, the burning of witches, the imprisonment of homosexuals, and the honor killing of unchaste sisters and daughters are just a few examples. (622)

The postmodern push to give precedence to moral and political considerations over science, reason, and fairness may seem like a good idea at first. But political ideologies can’t be defended on the grounds of their good intentions—they all have those. And morality has historically caused more harm than good. It’s only the minimalist, liberal morality that has any redemptive promise:

Though the net contribution of the human moral sense to human well-being may well be negative, on those occasions when it is suitably deployed it can claim some monumental advances, including the humanitarian reforms of the Enlightenment and the Rights Revolutions of recent decades. (622)

One of the problems with ideologies Pinker explores is that they lend themselves too readily to for-us-or-against-us divisions which piggyback on all our tribal instincts, leading to dehumanization of opponents as a step along the path to unrestrained violence. But, we may ask, isn’t the Enlightenment just another ideology? If not, is there some reliable way to distinguish an ideological movement from a “civilizing offensive” or a “Rights Revolution”? Pinker doesn’t answer these questions directly, but it’s in his discussion of the demonic side of morality where Better Angels offers its most profound insights—and it’s also where we start to be able to piece together the larger purpose of the book. He writes,

In The Blank Slate I argued that the modern denial of the dark side of human nature—the doctrine of the Noble Savage—was a reaction against the romantic militarism, hydraulic theories of aggression, and glorification of struggle and strife that had been popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Scientists and scholars who question the modern doctrine have been accused of justifying violence and have been subjected to vilification, blood libel, and physical assault. The Noble Savage myth appears to be another instance of an antiviolence movement leaving a cultural legacy of propriety and taboo. (488)

Since Pinker figured that what he and his fellow evolutionary psychologists kept running up against was akin to the repulsion people feel against poor table manners or kids winging balls at each other in gym class, he reasoned that he ought to be able to simply explain to the critics that evolutionary psychologists have no intention of justifying, or even encouraging complacency toward, the dark side of human nature. “But I am now convinced,” he writes after more than a decade of trying to explain himself, “that a denial of the human capacity for evil runs even deeper, and may itself be a feature of human nature” (488). That feature, he goes on to explain, makes us feel compelled to label as evil anyone who tries to explain evil scientifically—because evil as a cosmic force beyond the reach of human understanding plays an indispensable role in group identity.

Pinker began to fully appreciate the nature of the resistance to letting biology into discussions of human harm-doing when he read about the work of psychologist Roy Baumeister exploring the wide discrepancies in accounts of anger-inducing incidents between perpetrators and victims. The first studies looked at responses to minor offenses, but Baumeister went on to present evidence that the pattern, which Pinker labels the “Moralization Gap,” can be scaled up to describe societal attitudes toward historical atrocities. Pinker explains,

The Moralization Gap consists of complementary bargaining tactics in the negotiation for recompense between a victim and a perpetrator. Like opposing counsel in a lawsuit over a tort, the social plaintiff will emphasize the deliberateness, or at least the depraved indifference, of the defendant’s action, together with the pain and suffering the plaintiff endures. The social defendant will emphasize the reasonableness or unavoidability of the action, and will minimize the plaintiff’s pain and suffering. The competing framings shape the negotiations over amends, and also play to the gallery in a competition for their sympathy and for a reputation as a responsible reciprocator. (491)

Another of the Inner Demons Pinker suggests plays a key role in human violence is the drive for dominance, which he explains operates not just at the level of the individual but at that of the group to which he or she belongs. We want our group, however we understand it in the immediate context, to rest comfortably atop a hierarchy of other groups. What happens is that the Moralization Gap gets mingled with this drive to establish individual and group superiority. You see this dynamic playing out even in national conflicts. Pinker points out,