READING SUBTLY

This

was the domain of my Blogger site from 2009 to 2018, when I moved to this domain and started

The Storytelling Ape

. The search option should help you find any of the old posts you're looking for.

“The World until Yesterday” and the Great Anthropology Divide: Wade Davis’s and James C. Scott’s Bizarre and Dishonest Reviews of Jared Diamond’s Work

The field of anthropology is divided into two rival factions, the postmodernists and the scientists—though the postmodernists like to insist they’re being scientific as well. The divide can be seen in critiques of Jared Diamond’s “The World until Yesterday.”

Cultural anthropology has for some time been divided into two groups. The first attempts to understand cultural variation empirically by incorporating it into theories of human evolution and ecological adaptation. The second merely celebrates cultural diversity, and its members are quick to attack any findings or arguments by those in the first group that can in any way be construed as unflattering to the cultures being studied. (This dichotomy is intended to serve as a useful, and only slight, oversimplification.)

Jared Diamond’s scholarship in anthropology places him squarely in the first group. Yet he manages to thwart many of the assumptions held by those in the second group because he studiously avoids the sins of racism and biological determinism they insist every last member of the first group is guilty of. Rather than seeing his work as an exemplar or as evidence that the field is amenable to scientific investigation, however, members of the second group invent crimes and victims so they can continue insisting there’s something immoral about scientific anthropology (though the second group, oddly enough, claims that designation as well).

Diamond is not an anthropologist by training, but his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel, in which he sets out to explain why some societies became technologically advanced conquerors over the past 10,000 years while others maintained their hunter-gatherer lifestyles, became a classic in the field almost as soon as it was published in 1997. His interest in cultural variation arose in large part out of his experiences traveling through New Guinea, the most culturally diverse region of the planet, to conduct ornithological research. By the time he published his first book about human evolution, The Third Chimpanzee, at age 54, he’d spent more time among people from a more diverse set of cultures than many anthropologists do over their entire careers.

In his latest book, The World until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies?, Diamond compares the lifestyles of people living in modern industrialized societies with those of people who rely on hunting and gathering or horticultural subsistence strategies. His first aim is simply to highlight the differences, since the way most us live today is, evolutionarily speaking, a very recent development; his second is to show that certain traditional practices may actually lead to greater well-being, and may thus be advantageous if adopted by those of us living in advanced civilizations.

Obviously, Diamond’s approach has certain limitations, chief among them that it affords him little space for in-depth explorations of individual cultures. Instead, he attempts to identify general patterns that apply to traditional societies all over the world. What this means in the context of the great divide in anthropology is that no sooner had Diamond set pen to paper than he’d fallen afoul of the most passionately held convictions of the second group, who bristle at any discussion of universal trends in human societies. The anthropologist Wade Davis’s review of The World until Yesterday in The Guardian is extremely helpful for anyone hoping to appreciate the differences between the two camps because it exemplifies nearly all of the features of this type of historical particularism, with one exception: it’s clearly, even gracefully, written. But this isn’t to say Davis is at all straightforward about his own positions, which you have to read between the lines to glean. Situating the commitment to avoid general theories and focus instead on celebrating the details in a historical context, Davis writes,

This ethnographic orientation, distilled in the concept of cultural relativism, was a radical departure, as unique in its way as was Einstein’s theory of relativity in the field of physics. It became the central revelation of modern anthropology. Cultures do not exist in some absolute sense; each is but a model of reality, the consequence of one particular set of intellectual and spiritual choices made, however successfully, many generations before. The goal of the anthropologist is not just to decipher the exotic other, but also to embrace the wonder of distinct and novel cultural possibilities, that we might enrich our understanding of human nature and just possibly liberate ourselves from cultural myopia, the parochial tyranny that has haunted humanity since the birth of memory.

This stance with regard to other cultures sounds viable enough—it even seems admirable. But Davis is saying something more radical than you may think at first glance. He’s claiming that cultural differences can have no explanations because they arise out of “intellectual and spiritual choices.” It must be pointed out as well that he’s profoundly confused about how relativity in physics relates to—or doesn’t relate to—cultural relativity in anthropology. Einstein discovered that time is relative with regard to velocity compared to a constant speed of light, so the faster one travels the more slowly time advances. Since this rule applies the same everywhere in the universe, the theory actually works much better as an analogy for the types of generalization Diamond tries to discover than it does for the idea that no such generalizations can be discovered. Cultural relativism is not a “revelation” about whether or not cultures can be said to exist or not; it’s a principle that enjoins us to try to understand other cultures on their own terms, not as deviations from our own. Diamond appreciates this principle—he just doesn’t take it to as great an extreme as Davis and the other anthropologists in his camp.

The idea that cultures don’t exist in any absolute sense implies that comparing one culture to another won’t result in any meaningful or valid insights. But this isn’t a finding or a discovery, as Davis suggests; it’s an a priori conviction. For anthropologists in Davis’s camp, as soon as you start looking outside of a particular culture for an explanation of how it became what it is, you’re no longer looking to understand that culture on its own terms; you’re instead imposing outside ideas and outside values on it. So the simple act of trying to think about variation in a scientific way automatically makes you guilty of a subtle form of colonization. Davis writes,

The very premise of Guns, Germs, and Steel is that a hierarchy of progress exists in the realm of culture, with measures of success that are exclusively material and technological; the fascinating intellectual challenge is to determine just why the west ended up on top. In the posing of this question, Diamond evokes 19th-century thinking that modern anthropology fundamentally rejects. The triumph of secular materialism may be the conceit of modernity, but it does very little to unveil the essence of culture or to account for its diversity and complexity.

For Davis, comparison automatically implies assignment of relative values. But, if we agree that two things can be different without one being superior, we must conclude that Davis is simply being dishonest, because you don’t have to read beyond the Prelude to Guns, Germs, and Steel to find Diamond’s explicit disavowal of this premise that supposedly underlies the entire book:

…don’t words such as “civilization,” and phrases such as “rise of civilization,” convey the false impression that civilization is good, tribal hunter-gatherers are miserable, and history for the past 13,000 years has involved progress toward greater human happiness? In fact, I do not assume that industrialized states are “better” than hunter-gatherer tribes, or that the abandonment of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle for iron-based statehood represents “progress,” or that it has led to an increase in happiness. My own impression, from having divided my life between United States cities and New Guinea villages, is that the so-called blessings of civilization are mixed. For example, compared with hunter-gatherers, citizens of modern industrialized states enjoy better medical care, lower risk of death by homicide, and a longer life span, but receive much less social support from friendships and extended families. My motive for investigating these geographic differences in human societies is not to celebrate one type of society over another but simply to understand what happened in history. (18)

For Davis and those sharing his postmodern ideology, this type of dishonesty is acceptable because they believe the political ends of protecting indigenous peoples from exploitation justifies their deceitful means. In other words, they’re placing their political goals before their scholarly or scientific ones. Davis argues that the only viable course is to let people from various cultures speak for themselves, since facts and theories in the wrong hands will inevitably lubricate the already slippery slope to colonialism and exploitation. Even Diamond’s theories about environmental influences, in this light, can be dangerous. Davis writes,

In accounting for their simple material culture, their failure to develop writing or agriculture, he laudably rejects notions of race, noting that there is no correlation between intelligence and technological prowess. Yet in seeking ecological and climatic explanations for the development of their way of life, he is as certain of their essential primitiveness as were the early European settlers who remained unconvinced that Aborigines were human beings. The thought that the hundreds of distinct tribes of Australia might simply represent different ways of being, embodying the consequences of unique sets of intellectual and spiritual choices, does not seem to have occurred to him.

Davis is rather deviously suggesting a kinship between Diamond and the evil colonialists of yore, but the connection rests on a non sequitur, that positing environmental explanations of cultural differences necessarily implies primitiveness on the part of the “lesser” culture.

Davis doesn’t explicitly say anywhere in his review that all scientific explanations are colonialist, but once you rule out biological, cognitive, environmental, and climatic theories, well, there’s not much left. Davis’s rival explanation, such as it is, posits a series of collective choices made over the course of history, which in a sense must be true. But it merely begs the question of what precisely led the people to make those choices, and this question inevitably brings us back to all those factors Diamond weighs as potential explanations. Davis could have made the point that not every aspect of every cultural can be explained by ecological factors—but Diamond never suggests otherwise. Citing the example of Kaulong widow strangling in The World until Yesterday, Diamond writes that there’s no reason to believe the practice is in any way adaptive and admits that it can only be “an independent historical cultural trait that arose for some unknown reason in that particular area of New Britain” (21).

I hope we can all agree that harming or exploiting indigenous peoples in any part of the world is wrong and that we should support the implementation of policies that protect them and their ways of life (as long as those ways don’t involve violations of anyone’s rights as a human—yes, that moral imperative supersedes cultural relativism, fears of colonialism be damned). But the idea that trying to understand cultural variation scientifically always and everywhere undermines the dignity of people living in non-Western cultures is the logical equivalent of insisting that trying to understand variations in peoples’ personalities through empirical methods is an affront to their agency and freedom to make choices as individuals. If the position of these political-activist anthropologists had any validity, it would undermine the entire field of psychology, and for that matter the social sciences in general. It’s safe to assume that the opacity that typifies these anthropologists’ writing is meant to protect their ideas from obvious objections like this one.

As well as Davis writes, it’s nonetheless difficult to figure out what his specific problems with Diamond’s book are. At one point he complains, “Traditional societies do not exist to help us tweak our lives as we emulate a few of their cultural practices. They remind us that our way is not the only way.” Fair enough—but then he concludes with a passage that seems startlingly close to a summation of Diamond’s own thesis.

The voices of traditional societies ultimately matter because they can still remind us that there are indeed alternatives, other ways of orienting human beings in social, spiritual and ecological space… By their very existence the diverse cultures of the world bear witness to the folly of those who say that we cannot change, as we all know we must, the fundamental manner in which we inhabit this planet. This is a sentiment that Jared Diamond, a deeply humane and committed conservationist, would surely endorse.

On the surface, it seems like Davis isn’t even disagreeing with Diamond. What he’s not saying explicitly, however, but hopes nonetheless that we understand is that sampling or experiencing other cultures is great—but explaining them is evil.

Davis’s review was published in January of 2013, and its main points have been echoed by several other anti-scientific anthropologists—but perhaps none so eminent as the Yale Professor of Anthropology and Political Science, James C. Scott, whose review, “Crops, Towns, Government,” appeared in the London Review of Books in November. After praising Diamond’s plea for the preservation of vanishing languages, Scott begins complaining about the idea that modern traditional societies offer us any evidence at all about how our ancestors lived. He writes of Diamond,

He imagines he can triangulate his way to the deep past by assuming that contemporary hunter-gatherer societies are ‘our living ancestors’, that they show what we were like before we discovered crops, towns and government. This assumption rests on the indefensible premise that contemporary hunter-gatherer societies are survivals, museum exhibits of the way life was lived for the entirety of human history ‘until yesterday’–preserved in amber for our examination.

Don’t be fooled by those lonely English quotation marks—Diamond never makes this mistake, nor does his argument rest on any such premise. Scott is simply being dishonest. In the first chapter of The World until Yesterday, Diamond explains why he wanted to write about the types of changes that took place in New Guinea between the first contact with Westerners in 1931 and today. “New Guinea is in some respects,” he writes, “a window onto the human world as it was until a mere yesterday, measured against a time scale of the 6,000,000 years of human evolution.” He follows this line with a parenthetical, “(I emphasize ‘in some respects’—of course the New Guinea Highlands of 1931 were not an unchanged world of yesterday)” (5-6). It’s clear he added this line because he was anticipating criticisms like Davis’s and Scott’s.

The confusion arises from Scott’s conflation of the cultures and lifestyles Diamond describes with the individuals representing them. Diamond assumes that factors like population size, social stratification, and level of technological advancement have a profound influence on culture. So, if we want to know about our ancestors, we need to look to societies living in conditions similar to the ones they must’ve lived in with regard to just these types of factors. In another bid to ward off the types of criticism he knows to expect from anthropologists like Scott and Davis, he includes a footnote in his introduction which explains precisely what he’s interested in.

By the terms “traditional” and “small-scale” societies, which I shall use throughout this book, I mean past and present societies living at low population densities in small groups ranging from a few dozen to a few thousand people, subsisting by hunting-gathering or by farming or herding, and transformed to a limited degree by contact with large, Westernized, industrial societies. In reality, all such traditional societies still existing today have been at least partly modified by contact, and could alternatively be described as “transitional” rather than “traditional” societies, but they often still retain many features and social processes of the small societies of the past. I contrast traditional small-scale societies with “Westernized” societies, by which I mean the large modern industrial societies run by state governments, familiar to readers of this book as the societies in which most of my readers now live. They are termed “Westernized” because important features of those societies (such as the Industrial Revolution and public health) arose first in Western Europe in the 1700s and 1800s, and spread from there overseas to many other countries. (6)

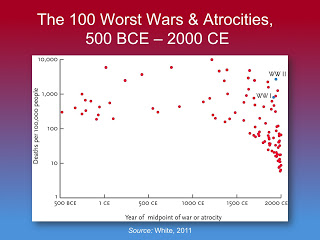

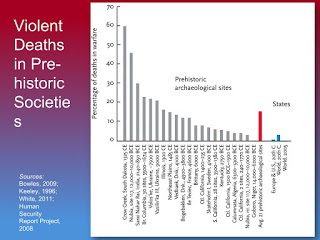

Scott goes on to take Diamond to task for suggesting that traditional societies are more violent than modern industrialized societies. This is perhaps the most incendiary point of disagreement between the factions on either side of the anthropology divide. The political activists worry that if anthropologists claim indigenous peoples are more violent outsiders will take it as justification to pacify them, which has historically meant armed invasion and displacement. Since the stakes are so high, Scott has no compunctions about misrepresenting Diamond’s arguments. “There is, contra Diamond,” he writes, “a strong case that might be made for the relative non-violence and physical well-being of contemporary hunters and gatherers when compared with the early agrarian states.”

Well, no, not contra Diamond, who only compares traditional societies to modern Westernized states, like the ones his readers live in, not early agrarian ones. Scott is referring to Diamond's theories about the initial transition to states, claiming that interstate violence negates the benefits of any pacifying central authority. But it may still be better to live under the threat of infrequent state warfare than of much more frequent ambushes or retaliatory attacks by nearby tribes. Scott also suggests that records of high rates of enslavement in early states somehow undermine the case for more homicide in traditional societies, but again Diamond doesn’t discuss early states. Diamond would probably agree that slavery, in the context of his theories, is an interesting topic, but it's hardly the fatal flaw in his ideas Scott makes it out to be.

The misrepresentations extend beyond Diamond’s arguments to encompass the evidence he builds them on. Scott insists it’s all anecdotal, pseudoscientific, and extremely limited in scope. His biggest mistake here is to pull Steven Pinker into the argument, a psychologist whose name alone may tar Diamond’s book in the eyes of anthropologists who share Scott’s ideology, but for anyone else, especially if they’ve actually read Pinker’s work, that name lends further credence to Diamond’s case. (Pinker has actually done the math on whether your chances of dying a violent death are better or worse in different types of society.) Scott writes,

Having chosen some rather bellicose societies (the Dani, the Yanomamo) as illustrations, and larded his account with anecdotal evidence from informants, he reaches the same conclusion as Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: we know, on the basis of certain contemporary hunter-gatherers, that our ancestors were violent and homicidal and that they have only recently (very recently in Pinker’s account) been pacified and civilised by the state. Life without the state is nasty, brutish and short.

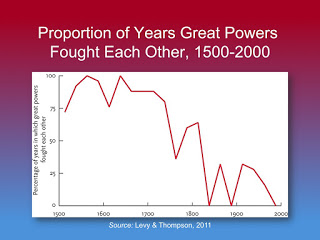

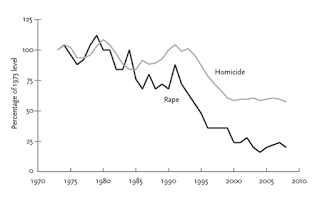

In reality, both Diamond and Pinker rely on evidence from a herculean variety of sources going well beyond contemporary ethnographies. To cite just one example Scott neglects to mention, an article by Samuel Bowles published in the journal Science in 2009 examines the rates of death by violence at several prehistoric sites and shows that they’re startlingly similar to those found among modern hunter-gatherers. Insofar as Scott even mentions archeological evidence, it's merely to insist on its worthlessness. Anyone who reads The World until Yesterday after reading Scott’s review will be astonished by how nuanced Diamond’s section on violence actually is. Taking up almost a hundred pages, it is far more insightful and better supported than the essay that purports to undermine it. The section also shows, contra Scott, that Diamond is well aware of all the difficulties and dangers of trying to arrive at conclusions based on any one line of evidence—which is precisely why he follows as many lines as are available to him.

However, even if we accept that traditional societies really are more violent, it could still be the case that tribal conflicts are caused, or at least intensified, through contact with large-scale societies. In order to make this argument, though, political-activist anthropologists must shift their position from claiming that no evidence of violence exists to claiming that the evidence is meaningless or misleading. Scott writes,

No matter how one defines violence and warfare in existing hunter-gatherer societies, the greater part of it by far can be shown to be an effect of the perils and opportunities represented by a world of states. A great deal of the warfare among the Yanomamo was, in this sense, initiated to monopolise key commodities on the trade routes to commercial outlets (see, for example, R. Brian Ferguson’s Yanomami Warfare: A Political History, a strong antidote to the pseudo-scientific account of Napoleon Chagnon on which Diamond relies heavily).

It’s true that Ferguson puts forth a rival theory for warfare among the Yanomamö—and the political-activist anthropologists hold him up as a hero for doing so. (At least one Yanomamö man insisted, in response to Chagnon’s badgering questions about why they fought so much, that it had nothing to do with commodities—they raided other villages for women.) But Ferguson’s work hardly settles the debate. Why, for instance, do the patterns of violence appear in traditional societies all over the world, regardless of which state societies they’re in supposed contact with? And state governments don’t just influence violence in an upward direction. As Diamond points out, “State governments routinely adopt a conscious policy of ending traditional warfare: for example, the first goal of 20th-Century Australian patrol officers in the Territory of Papua New Guinea, on entering a new area, was to stop warfare and cannibalism” (133-4).

What is the proper moral stance anthropologists should take with regard to people living in traditional societies? Should they make it their priority to report the findings of their inquiries honestly? Or should they prioritize their role as advocates for indigenous people’s rights? These are fair questions—and they take on a great deal of added gravity when you consider the history, not to mention the ongoing examples, of how indigenous peoples have suffered at the hands of peoples from Western societies. The answers hinge on how much influence anthropologists currently have on policies that impact traditional societies and on whether science, or Western culture in general, is by its very nature somehow harmful to indigenous peoples. Scott’s and Davis’s positions on both of these issues are clear. Scott writes,

Contemporary hunter-gatherer life can tell us a great deal about the world of states and empires but it can tell us nothing at all about our prehistory. We have virtually no credible evidence about the world until yesterday and, until we do, the only defensible intellectual position is to shut up.

Scott’s argument raises two further questions: when and from where can we count on the “credible evidence” to start rolling in? His “only defensible intellectual position” isn’t that we should reserve judgment or hold off trying to arrive at explanations; it’s that we shouldn’t bother trying to judge the merits of the evidence and that any attempts at explanation are hopeless. This isn’t an intellectual position at all—it’s an obvious endorsement of anti-intellectualism. What Scott really means is that he believes making questions about our hunter-gatherer ancestors off-limits is the only morally defensible position.

It’s easy to conjure up mental images of the horrors inflicted on native peoples by western explorers and colonial institutions. But framing the history of encounters between peoples with varying levels of technological advancement as one long Manichean tragedy of evil imperialists having their rapacious and murderous way with perfectly innocent noble savages risks trivializing important elements of both types of culture. Traditional societies aren’t peaceful utopias. Western societies and Western governments aren’t mere engines of oppression. Most importantly, while it may be true that science can be—and sometimes is—coopted to serve oppressive or exploitative ends, there’s nothing inherently harmful or immoral about science, which can just as well be used to counter arguments for the mistreatment of one group of people by another. To anthropologists like Davis and Scott, human behavior is something to stand in spiritual awe of, indigenous societies something to experience religious guilt about, in any case not anything to profane with dirty, mechanistic explanations. But, for all their declamations about the evils of thinking that any particular culture can in any sense be said to be inferior to another, they have a pretty dim view of our own.

It may be simple pride that makes it hard for Scott to accept that gold miners in Brazil weren’t sitting around waiting for some prominent anthropologist at the University of Michigan, or UCLA, or Yale, to publish an article in Science about Yanomamö violence to give them proper justification to use their superior weapons to displace the people living on prime locations. The sad fact is, if the motivation to exploit indigenous peoples is strong enough, and if the moral and political opposition isn’t sufficient, justifications will be found regardless of which anthropologist decides to publish on which topics. But the crucial point Scott misses is that our moral and political opposition cannot be founded on dishonest representations or willful blindness regarding the behaviors, good or bad, of the people we would protect. To understand why this is so, and because Scott embarrassed himself with his childishness, embarrassed The London Review which failed to properly fact-check his article, and did a disservice to the discipline of anthropology by attempting to shout down an honest and humane scholar he disagrees with, it's only fitting that we turn to a passage in The World until Yesterday Scott should have paid more attention to. “I sympathize with scholars outraged by the mistreatment of indigenous peoples,” Diamond writes,

But denying the reality of traditional warfare because of political misuse of its reality is a bad strategy, for the same reason that denying any other reality for any other laudable political goal is a bad strategy. The reason not to mistreat indigenous people is not that they are falsely accused of being warlike, but that it’s unjust to mistreat them. The facts about traditional warfare, just like the facts about any other controversial phenomenon that can be observed and studied, are likely eventually to come out. When they do come out, if scholars have been denying traditional warfare’s reality for laudable political reasons, the discovery of the facts will undermine the laudable political goals. The rights of indigenous people should be asserted on moral grounds, not by making untrue claims susceptible to refutation. (153-4)

Also read:

NAPOLEON CHAGNON'S CRUCIBLE AND THE ONGOING EPIDEMIC OF MORALIZING HYSTERIA IN ACADEMIA

And:

THE SELF-RIGHTEOUSNESS INSTINCT: STEVEN PINKER ON THE BETTER ANGELS OF MODERNITY AND THE EVILS OF MORALITY

And:

Encounters, Inc. Part 2 of 2

The relationship between Tom and Ashley (Monster Face) heats up as Jim keeps getting in deeper and deeper, even though Marcus is looking ever more shady.

The way it’s going to go down is that some detective will show up at the local headquarters of Marcus’s phone service provider, produce the necessary documents—or the proper dose of intimidation—and in return receive a stack of paper or a digital file listing the numbers of every call and text sent both to and from his phone. The detective will see that my own number appears in connection with the ill-fated outing enough times to warrant bringing me in for questioning. So now I’m wondering for the first time in my life if I have what it takes to lie to police detectives. Does a town like Fort Wayne employ expert interrogators? Of course, if I happen to have mentioned the murder in any of the texts, I can’t very well claim I didn’t know about it. Maybe I should call a lawyer—but if I do that before the detective knocks on my door I’ll have established for everyone that I’m at least guilty of something.

Then there are the emails, where we conducted most of our business. If the NSA can get into emails, it can’t be that difficult for the FWPD to do it. But will they be admissible? If not, do they point the way to any other evidence that is? Just to be safe, it’s probably time to go in and delete all of Marcus’s messages in my inbox—not that it will do much good, not that it will make me feel much better.

Hey Jim,

I love your ideas for the website, esp the one about a section for all the local lore by region—the stuff about how you cross this bridge in your car and turn off your lights to see the ghost of some lady (Lagrange?), or look over the side of the bridge and say some name three times and the eyes appear in the water (Huntertown?). People love that kind of stuff. It may not appeal to grownups as much, but we can still use it to drive traffic—or hell we could even sell the ebooks like you suggest.

You may be getting carried away with the all independent publishing stuff tho. I’m not sure, but it sounds like it’s just getting too far afield, you know? Let’s just say you haven’t sold me on it yet. Is there some way you can tie it all together? My concern is that if we start pushing out fiction it will detract from the… what’s the word? Authenticity? The authenticity of the experiences we’re providing our clients. I don’t know—tell me more about your vision for how this would work.

Anyway, love the dream stuff. You’re cranking this stuff out faster than I could’ve anticipated. One thing—and I’m very serious here—don’t go down there. Don’t go anywhere near the base of the Thieme Overlook. I’ll just say you don’t have all the details, don’t know the whole story yet. Patience my man.

Best,

Marcus

Jim,

Lol. Well, I’m glad you didn’t come to any harm on your little trek down to the Saint Mary’s. That’s all I’ll say about it for now—except you’ll just have to trust me that there not being anything down there doesn’t mean we don’t have a story. You’ve obviously caught the inquisitive bug that’s going around. But I have to say we should probably respect Tom’s wishes and leave Ashley out of it. Let’s focus on the ghost story and not get too carried away with the sleuthing. Besides, you need to have something ready in just a couple weeks for our first outing.

As far as the final details of the story go—I believe Tom might be eager to do some further unburdening.

Best,

Marcus

I had a hard time accepting that Ashley would do anything as outright sadistic as she’d done that night when she provoked those two men—not without giving Tom at least some indication of what had prompted her to do it. Again and again, he swore he really didn’t know what could’ve motivated her, but as I kept pressing him, throwing out my own attempted explanations one after the other, his dismissals began to converge on a single new most likely explanation. “It was like when I yelled at her that same night,” he said. “I always got this sense that she was slightly threatened by me. I’m pretty opinionated and outspoken—and I’m nothing like the people she and I both used to work with at the restaurants.”

Tom had the rare distinction among his classmates in the MBA program of being a fervent liberal. His views had begun to take shape as early as his undergrad years, when he absorbed the attitude toward religion and so-called family values popular among campus intellectuals. The farther he moved ideologically from the Catholicism he was raised to believe, the more resentful he became of Christianity and religion in general. “It’s too complicated to go into now,” he told me. “But it was like I was realizing that what was supposed to be the source of all morality was in reality fundamentally immoral—hypocritical to the core. You know, what’s all this nonsense about Jesus being tortured and executed because Eve ate some damn apple—this horrible crime you’re somehow still guilty of even if you were born thousands of years after it all happened? I mean, it’s completely insane.”

The economic side to Tom’s political leanings was shaped by his experiences with a woman he’d oscillated between dating and being friends with going all the way back to his sophomore year in high school. In her early twenties, she started having severe pain during her periods. It got so bad on a few occasions that it landed her in the ER. She ended up being treated for endometriosis, and to this day (Tom had spoken to her as recently as a month and half before she came up in our interview) her ability to conceive is in doubt. The ordeal lasted for over a year and half, which would have been bad enough, but at the time it began she had just been kicked off her dad’s insurance coverage. Try as she might, it wouldn’t be until five years later, after she’d been forced to declare bankruptcy—and after Tom had devoted a substantial chunk of his own student loans to helping her—that she’d finally have health insurance again. “It’s inhuman,” Tom said. “Tell me, how does supply-and-demand work with healthcare? What’s the demand? Not wanting to die? And how the hell does fucking personal responsibility come into the equation? Do republicans really think they can will themselves healthy?”

Over the course of all the presidential and midterm elections that resulted in Obamacare becoming the law of the land, Tom acquired a reputation as someone to be avoided, particularly if you were a conservative—or maybe I should say particularly if you were only halfheartedly political. And it wasn’t just healthcare. He was known to have brought people to tears in debates over economic inequality, racial profiling, education reform, wage gaps between men and women, whites and minorities, corporatism, plutocracy, white warlike men wearing the mantle of righteousness as they persisted in wielding their unwarranted power—just in ever more subtle and devious ways. Even though I, your humble narrator, voiced no opposition to his charged declamations, he still managed to make me slightly uneasy. I could even see a type of perverse logic in the way Ashley expressed her exasperation, forcing this saintly advocate for all things rational and humane to kick the shit out of a couple white trash wastoids.

It was a lesson for me in the power of circumstance over personality—he’d originally struck me as so humble and mindfully soft-spoken, or perhaps simply restrained—and it set my mind to work disentangling the various threads of his character: fascinated with combat sports but loath to do harm, a marketer with an MBA who rants about the evils of capitalism, a champion for the cause of women and minorities who gives no indication of having a clue when it comes to either. I even weighed the possibility that he may have been less than forthright with me, and with himself, when he spoke of having no blood in his eye. Had he just been trying to prove something?

On the same night he told me the story of the two men who’d attacked him and Ashley outside Henry’s, Tom told me about another encounter he’d had a year earlier that could also have ended in violence. He was clearly trying to prevent an impression of him as a violent man from becoming cemented in my mind, and he was at the same time emphasizing just how impossible it was to figure out what Ashley ever really wanted from him. But it came to mind after I made the discovery about his ardently fractious inclinations as possibly holding some key to his paradoxical character.

Tom and Ashley had walked from West Central to the Three-Rivers Natural Food Co-op and Deli (which they referred to affectionately as “The Coop”) for lunch on a sweltering summer afternoon. As he stood in line to order their sandwiches, he let his eyes wander idly around until they lit on those of another man who appeared to be letting his own eyes wander in the same fashion. Tom gave a nod and turned back to face the counter and the person in front of him in line. But the eye contact hadn’t been purely coincidental; after a moment, the man was sidling up and offhandedly inquiring whether Tom would be willing to buy him a pack of cigarettes. Tom leaned back and laughed through his nose. “What’s so funny?” the man asked, making a performance of his indignation. After Tom explained that they were standing in a health food store that most certainly didn’t sell cigarettes, the man said, “You can still help me out with a couple bucks” in a tone conveying his insufferable grievance.

Ashley appeared beside Tom just as he was saying, “I’ll buy you a sandwich or something, but I’m not giving you any money.” She was either already annoyed by something else, or became so immediately upon hearing him, making him wonder if the offer of the sandwich had been inadvisable, or if maybe he hadn’t rebuffed the supplication with enough force.

“I don’t need no damn sandwich,” the man said, making an even bigger production of how offended he was. He stood watching Tom for several beats before wandering off in a silent huff, like a chided but defiant child appalled by his mother’s impudence in disciplining him.

By the time he was sitting down on the steel mesh chair across from Ashley at one of the Coop’s patio tables, Tom had decided the man was an experienced, though unskillful, grifter. A middle-aged African American, he’d planned to take advantage of Tom’s liberal eagerness to buddy up with any black guy. When that failed, he did his enactment of taking offense, so Tom might feel obliged and be so gracious as to make monetary amends. Finally, he must’ve considered making a scene but considered it unlikely to do any good now that Tom was stubbornly set on giving him the brush off. Ashley and Tom hadn’t even finished unwrapping their sandwiches when the guy emerged through the glass doors, walked a few steps to the bike rack on the sidewalk, and half-stood, half-sat with one leg resting atop the frame, glaring at Tom as he drank Sprite from its gleaming green bottle in tiny sips. So now the goal has shifted, Tom thought, to saving face.

The guy had a film on his skin that, along with the trickling sweat, evoked in Tom’s mind an image of rain misting in through a carelessly unclosed window onto a dusty finished-wood surface. His clothes looked as though they hadn’t been washed—or even removed—in weeks. With little more than a nudge, Tom figured he could knock the guy off the bike rack, his spindly legs having no chance of finding their way beneath him in time to keep him from landing on his face. Could he have a weapon? Tom considered his waxy eyes. Even if the guy has a gun or a knife, he reasoned, he wouldn’t be able to get to it in time to stop me from bouncing his head off the parking lot. Assured that the guy had no chance of winning a fight, Tom gave up the idea of fighting him. So the guy stayed there staring at the couple almost the whole time they were eating their lunch. As annoyed as Tom was, he was prepared to dismiss it all as a simple misfortune.

But that evening Ashley let him know she didn’t like how he’d handled it.

“What do you think I should have done?”

“I don’t know. I just didn’t like the way you handled it.”

***

“What I loved most about being with Ashley,” Tom said to me, “was there was always this sense that whatever we came across or encountered together held some special fascination for us. One of the first times I had the thought that things might be getting serious between us was when she took me to visit her grandmother up in… Ah, but you know, I’m going keep her personal details out of this I think. I’ll just say there was this feeling I had—like we were both kind of fusing or intertwining our life stories together. We would go on these walks that would end up lasting all day and take us miles and miles from where we started, and we’d never run out of things to talk about, and every little thing we saw seemed important because it automatically became part of the stories we were weaving together.”

When Tom and Ashley had been together for a couple of months, soon after the visit to her grandmother, he drove her to Union Chapel Road, in what had until recently been the northernmost part of the city, to show her the house he’d lived in for years and years, the place where he said he felt like he’d really become the man he was. After parking on a street in Burning Tree, the neighborhood whose entrance lies only a few dozen yards from his old driveway, they went for one of those walks, heading east on Union Chapel, the same way Tom used to go when embarking on one of his routine runs down to Metea Park and back, a circuit of about nine and half miles. Already by the time he was introducing the area to Ashley, he knew they would encounter a lot of construction and new housing developments once they crossed the bridge over Interstate 69. But he wasn’t sure if the one thing he most wanted to show her would still be there.

The area across from his old house had long since been developed, but once you crossed Auburn Road you saw nothing but driveways leading to single residences on either side of the road all the way up the rise to the bridge. On the other side of 69, Tom used to see open expanses of old farmland, but the steady march of development was moving west from Tonkel Road back toward the interstate. Back in the days of his runs, just down the slope on the west side of the bridge, a line of pine trees would come into view beginning on the left side of Union Chapel and heading north. “I ran past it for years and never really noticed it much,” Tom said. “I always go into these trances when I’m running. I think I may have even realized it was a driveway only long after my run one day, when I was back home doing something else.”

The pines, he would discover, ran along both sides of a gravel drive that took you about a quarter mile up a rise into the old farmland and then split apart to form the base of an enclosed square. “It’s the oddest looking thing, right in the middle of all this open space at the top of a hill you almost can’t see for all the weeds. I can’t believe how many times I just ran right by it and never really thought about how weird it was.” In the middle of the square stood an old two-story house, white with gray splotches, and what used to be a lawn now overtaken by the relentlessly encroaching weeds. Tom had finally decided to turn into the drive one day while on his way back from Metea, and ended up remembering it ever since, even though he never returned—not until the day he walked there with Ashley.

As August was coming to an end that year, Tom had begun to feel a nostalgic longing, not for the classes and schoolwork he’d been so relieved to be done with forever just the year before, but for the anticipation of that abstract sense of personal expansion, the promise every upcoming semester holds for new faces, new books, new journeys. As long as you’re in school, you feel you’re working toward something; your life has a gratifying undercurrent of steady improvement, of progress along the path toward some meaningful goal. Outside of school, as Tom was discovering, every job you start, every habit you allow yourself to carry on, pretty much everything you do comes with the added weight of contemplating that this is what your life is and this is what your life is always going to be—a flat line.

Back in June of that year, the woman Tom had been in an on-again-off-again relationship with almost his entire adolescent and adult life, the one whose health issues had forced to declare bankruptcy, had moved to Charlotte to live with her mom and little sister. He wanted to see his freshly unattached and unencumbered life as at long last open to the infinite opportunity he’d associated in his mind with adulthood for as long as he could remember, the blank canvas for the masterpiece he would make of his own biography. Instead, all summer he’d been oppressed by incessant misgivings, a paralytic foreboding sense of already knowing exactly where all the paths open before him ultimately led.

It was on a day when this foreboding weighed on him with a runaway self-feeding intensity that Tom determined to go for his customary run despite the forecasted rain. By the time he’d made it all the way to Metea and more than halfway back, finding himself near the entrance of the remarkable but long unremarked tree-lined driveway, after having been all the while in a blind trance more like a dreamless sleep than the meditative nirvana he’d been counting on, he was having hitches in his breath, as if he were on the verge of breaking into sobs. The sky had gone from that rich glassy blue that heralds early fall to an oppressively overcast gray more reminiscent of deepest summer, the air ominously swelling with a heavy pressurized dankness that crowded out all the oxygen and clung to Tom’s chilled and sweat-drenched shoulders in a way that made him feel as though the skin there had been perforated to allow his watery innards to seep upward in a hopeless effort to evaporate. It was a sensation indistinguishable from his thwarted urge to escape this body of his he knew too well, along with the world and everything in it.

Turning into the drive, he maintained his stride and continued running until he was about halfway up the rise, where he surprised himself by pulling back against the rolling momentum of his legs and feet, tamping down the charged fury of his pace, until his numbly agitated legs were carrying him along with harshly chastened steps. “As I walked up to the house, I wondered what the story of the people who’d lived there was. And, seeing how rundown everything was, how the weeds were growing up all over the place, you know, it was just like, what does it even matter at this point what happened here? I had actually thought about showing the house to some of my friends, like one of those old spooky houses you’re fascinated with when you’re a kid. But, I don’t know, somehow it got folded into my mood, and all I saw was a place someone had probably loved that had gone to seed.”

Having lost all interest in further exploring the place, Tom was gearing up to start running again once he reached the end of the driveway. But just when he was about to turn back something caught his eye. “I remember telling Ashley about it as we were walking along the bridge over I-69 because she gave me this weird look. See, I explained that the flowers looked like some you see all the time in late summer and early fall. But whenever I’d seen them before they were always purple. These ones, I told her, were ‘as blue as the virgin’s veil.’ We’re both pretty anti-religion, so she thought the comparison was a bit suspicious. I had to assure her it was just an expression, that I wasn’t lapsing back into my childhood Catholicism or anything. To this day, I have no idea why that particular image popped into my head.”

Sure enough, when Tom returned that day years later with Ashley, the tree-lined drive, the graying house, and the blue wildflowers were all there just as he remembered them. Ashley recognized the species at a glance: “They’re actually called blue lobelias, but you’re right—they’re usually much closer to purple than blue.” Tom went on to recount how when he’d first discovered these three clusters near the head of the driveway he’d been feeling as though his whole body, his whole life, had somehow turned into a rickety old husk he had to drag around every waking hour. Setting out for his run that day, he’d experienced an upwelling of his longing to break out of it—to free himself. The heaviness of the atmosphere and the sight of the house only made it worse though. He’d felt like he was suffocating. When he saw the lobelias, it was at first simply a matter of thinking they looked unusual. But after squatting down for a closer look he stood up and took this gulping breath deep into the lowermost regions of his lungs.

“It was like I was drinking something in, like I no longer needed to escape because my body was being reinvigorated. All that dead weight was coming back to life. The change was so abrupt—I couldn’t have been in that yard for more than a few minutes—but I ended up running the rest of the way home with the cleared head I’d set out for in the first place. Even more than that, though, I experienced a sense of renewal that brought me out of the funk I’d been sunk in for weeks. It was only a few weeks later that I started working at the restaurant.

“Oh, and I can’t leave out how the rain began to fall just as I was within a hundred feet of the driveway at my own house.”

***

It was after conducting the interview about the old house on Union Chapel that I first started thinking about pulling out of Marcus’s haunted house business. Was I doing all this work for a story about a house that wouldn’t even be there six months from now? As far as knew, construction had already begun on a junction connecting Union Chapel with I-69. Hadn’t Marcus thought to consult with any locals about the location? And how would using the story for some other location affect the “authenticity” he was so concerned with? But the bigger issue was that, while I didn’t yet know the whole story, I was getting the impression it wasn’t really over—and now I was smack-dab in the middle of it. Looking Marcus up on LinkedIn again, I found that since the time he’d first contacted me, which was apparently only about a month after he moved to Fort Wayne from Terra Haute, he’d opened, ironically enough, his own coffee shop on Wells Street.

Back when he’d told me about the money he had saved up for his business venture, I imagined him sitting on a big pile of cash which would allow him to devote all his time to it. Now I was thinking that the whole endeavor, for all his high-wattage salesmanship, could only be a measly side project of his. Yet I was getting all these emails urging me to hurry up and get the story ready to send to all the people who’d already signed up for the first outing the weekend before Halloween. And then there were all the questions surrounding Tom and how he’d ended up coming into Marcus’s ambit. Tom had given us his consent to use his story, his sharing of which I had interpreted as an attempt at unburdening himself, to make of me and Marcus his surrogate confessors. But now I was no longer sure that what Marcus and I were doing met the strictest Capitalism 2.0 standards. I kept asking myself as I listened to the recordings, am I making myself complicit in some kind of exploitation? Should I be doing something more to help Tom—instead of trying to make money off of him?

***

In the days after Ashley broke up with Tom, as he settled into the new apartment by himself, he went nearly mad from lack of sleep. No sooner would he lie down and close his eyes than he would be wracked with jealous anxiety powered by images of Ashley with myriad other men he couldn’t help suspecting were the real motivation behind her decision to abandon him. The searing blade of his kicked-in rib, which flared up as if trying to tear free of his body whenever he lay flat or attempted to roll from one side to the other, robbed him of what little of the night’s sleep was left after the jealous heartbreak had taken its share. Desperate, he contacted an old friend from Munchies who came through for him with some mind-bogglingly potent weed. Over the next week, Tom managed to get plenty of sleep, and mysteriously managed as well to gain seven pounds.

One Sunday, Tom heard a knock on his apartment door, which meant one of his neighbors from the three other apartments in the house wanted something. When he opened the door to a tall, very dark-complexioned black man, he couldn’t conceal his surprise. “It’s okay my friend,” the visitor said with a heavy-consonanted accent Tom couldn’t place. “I’m Sara’s boyfriend—from across the hall.” Tom introduced himself and offered his hand. The man’s name was Luca or Lucas, and Tom would later learn that he’d come from the Dominican Republic or Haiti as a high school student, a move that was undertaken under the auspices of the Fort Wayne diocese of the Catholic church. “I noticed the smell of marijuana coming from your apartment the other night and I was wondering if you’d be willing to sell me a small amount.”

Tom gave Lucas all the weed he still had gratis. He would recount to his landlord two days later the story of how he’d been startled by the big black guy knocking on his door (without of course revealing the reason behind the visit), and in return hear what little the landlord knew about him, but, aside from that, he thought nothing further about it—until the following Sunday when he heard another knock on his door. Impatient, Tom opened the door prepared to explain that he had no more weed and didn’t know Lucas well enough to give him his source’s contact information. But Lucas barely let him open the door fully before thrusting a small green pouch into his chest. “Just a little thank you my friend. You’ll only get a couple of hits from that, but trust me. Save it for when you have no work in the morning.” Tom was ready to refuse the gift, but Lucas withdrew his hand and rushed downstairs and out the front door of the house so quickly all he had time to shout after him was thanks. It turned out Lucas and Sara had just broken up. That was the last Tom ever saw of him.

***

Marcus’s coffee shop was smaller and more dimly lit than Old Crown, but it had a certain undeniable charm. When I got there at a little after four in the afternoon, the place was completely empty except for the two young women working the counter. I asked the taller of the two if Marcus was around, but she responded by casting a worried look at her coworker. They both looked to be in their early to mid-twenties, and they were both strikingly attractive in a breezily unkempt sort of way. The shorter one seemed the sharper of the two, exuding a type of evaluating authority, sizing me up, silently challenging me to convince her I was worth the moment of her attention I had requested. Most restaurants and shops like this have a matriarch or two who are counted on to really run the place, the all-but-invariably male general manager’s official title notwithstanding. I guessed I was looking at just such a matriarch—and I suspected she might be romantically linked to Marcus too, an intuition I couldn’t rationally support, except perhaps by pointing to her seeming defensiveness at mention of his name. “No, he’s not in,” she said. “Is there anything we can help you with?”

I told her I was a friend and had learned about the coffee shop from Marcus’s LinkedIn profile, but leaving a message or even giving my name would be unnecessary. “I’m sure I’ll be back sometime.” I quickly scanned the chalkboard menu on the wall behind her for something to order, hoping to distract her enough to ward off any further questions. “Could I have a pumpkin spice latte please?” I browsed around while the taller barista made my latte and the shorter one returned to what she’d been doing before I arrived—it looked like she was reading from something concealed behind the counter, a book or a magazine perhaps. I constructed an image of her and a sense of her bearing over the course of several nonchalant sweeps of my eyes. She had what the guys in my circle call a monster face: rounded cheeks that lift high on her smoothly protrusive cheekbones when she smiles, pushing her outsize eyes into squinting crescents, a tiny chin topped by an amazingly expandable and dynamic press of lips. As pretty as she was, her face, especially when she smiled, bore the slightest resemblance to the Grinch’s. All in all, she seemed to have a big and formidable personality animating her small, even dainty body. I could see why Marcus would like her.

I took my latte over to a couch and set it on a coffee table so I could remove my laptop from my backpack and do some editing for the writing project you’re currently reading. Taking a moment to acknowledge the pumpkin spice’s justifiedly much-touted powers of evocation, I scanned line after line, simultaneously wondering how much Cute Monster Face knew about Marcus’s side venture. I realized that I couldn’t enquire after it though because I was worried about the legal ramifications if Tom’s deed came to light. And that realization transformed quickly into frustration with Marcus for getting me involved without properly disclosing the crucial details of what I was getting involved in. After finishing, as I stepped outside onto the sidewalk running along Wells Street, I considered going back in and penning a message:

Marcus,

I don’t appreciate you getting me tangled up in your shady operation. I’m out.

Jim

But I decided against it because I thought I should be fair and wait until I knew the rest of the story. It would be pretty low of me to leave him high-and-dry this close to the event. And, I admit it, I was just too damn curious about what had happened to Tom, and too damn curious as well about how Marcus’s endeavor would pan out. I went home and prepared for what would be my second-to-last interview with Tom.

***

“I’ve heard so many times about how I supposedly like to bully people,” Tom was telling me. “But I’ll never forget the feeling of my knuckles hacking into the flesh right behind that guy’s jaw. It all happened so fast with the two guys outside Henry’s, like it was over before I knew what was happening. With this guy, though—I’d been thinking about Ashley, about how much she misunderstood me, and how she of all people should’ve been able to see past what on the surface probably did look like bullying. I admit it. But that’s not what it was. That’s not ever what it was. Then I started wondering who she might be with at that same moment—I couldn’t help it. You know, you’re mind just sort of goes there no matter how hard you try to rein it in. I had all this rage surging up. All the streetlamps are leaving these slow-motion trails, my heart is banging on my ribs like some rabid ape trying to break out of its damn cage, and I keep closing my eyes—and it’s happening right in front of me. Ashley and some guy. Then I smelled somebody’s menthol cigarette—that’s when I opened my eyes.”

It had begun one evening in June while Tom was out for one of his nightly walks in West Central. What he found most soothing about these listless meanderings of his was being able to look straight up into the sky and see nothing but endless blue, an incomprehensible vastness the mere recognition of which created a sensation like an upward pull, as if the sheer immensity of the emptiness inhered with its own vacuuming force to counter the gravity of the solid earth. He liked going out when the drop in temperature could be most dramatically felt, when the vibrant azure of the day faded before his eyes to the darker, richer, fathomless hues of twilight—the airy insubstantial sea of white-cast blue drawn out through the gracelessly mended seam of the western horizon, a submerged wound which never heals and daily reopens to spill its irradiated blood into the coursing streams of air as they seep out over the edge of the world. Tom, stopping at the overlook each day for weeks to watch the molten pinks and oranges and startling crimsons bleed away the day’s final residue, was always surprised to be the only one in attendance.

But one night as he stood resting his elbows on the concrete railing he heard someone addressing him. “You guna jump?” Tom looked back over his shoulder without bothering to stand up from his leaning position and saw a heavy-set man with a bushy mess of a goatee waiting for an answer on the sidewalk behind him. He was shortish and had the look of a walking barrel. “He looked,” in Tom’s words, “quite a bit like Tank Abbott from some of the earlier UFCs.” Seeing that no one else was around for the man to be addressing, Tom turned and said, “Probably not today.”

“Oh, well, I think you should,” the man said, taking a couple of steps forward. He had a backpack slung over one shoulder and looked to be returning from work somewhere on the other side of the river.

Tom was reticent but couldn’t help asking, “Yeah, why is that?”

“Well, you’re probably thinking maybe things will be better tomorrow. But it doesn’t work that way as far as I know. Tomorrow, you’ll still be just as much of a faggot.”

Tom leaned back, resting both elbows on the rail, and leveled a steady glare at the man as he affected the profoundest boredom. The walking barrel responded by leaning slightly to the side and spitting on the ground between them. Then he continued walking down Thieme, leaving Tom free to wonder what had prompted the insult. His first thought was that this man might know one or both of the two guys he’d beat up that night after leaving Henry’s. But if that were the case he probably would’ve gone further than calling him a faggot. Tom figured it was just one of those things, and set to trying to push it out of his mind. He’d noted the knife clipped to the outside of the man’s right pants pocket, and he reasoned that since he was alone and hence not putting on a show for anyone, his goad must have been a genuine invitation to fight. Tom would have to watch out for him in the future.

But, as was his wont, Tom had gone into one of his walking trances some minutes before he encountered the barrel a second time. It was later that same week, which made Tom realize afterward that he could probably avoid further encounters by heading out for his walks at a different time of night. This second meeting had them crossing each other’s paths as they headed in opposite directions on the sidewalk along Thieme. “What’s up, faggot?” the barrel called out in greeting. Emerging instantly from his trance, Tom glared back at him. When they were face to face, within striking distance, the man jerked forward with his shoulders, trying to trick Tom into reacting as if he were lunging at him. Tom indeed turned sideways into a subtle crouch, flinching, which produced a broad self-amused grin on the barrel’s scraggly, egg-shaped face. “See you tomorrow faggot,” he said continuing past.

The barrel thus began haunting Tom while he was still very much alive, in the way that all men are haunted by insults they fail to, or choose not to redress. His strategy of avoidance felt like a breed of forced effacement, a step toward submission. He was going out later, missing the crepuscular displays over the treetops on the facing side of the Saint Mary’s, returning to his apartment just before going to bed, aggravating his already too wakeful condition. Every time he rounded the corner from Wayne Street onto Thieme Drive, Tom felt like he was stepping onto a sidewalk in a completely different city. Some evenings, he could even close his eyes and reopen them on an entirely different world. Behind the line of trees across the street, there was a type of void, a pressurized humming emptiness hovering over the imperceptibly slow-coursing river separating his neighborhood from the motley houses beyond the opposite bank. You could often hear the throb of bass in the distance, faraway rhythmical percussions made to seem primitive or otherworldly, catch whiffs of smoke from far-off bonfires, or pick up the tail end of some couple’s shouting match. It all resonated through that strange hollow space framed by the trees on each facing bank, making it seem somehow closer and at the same time farther away.

The old sycamores and random oaks along the walk, compared to all the other new-growth trees in the city, seemed prehistorically gargantuan, their branches reaching up like monstrous undulating tendrils toward the firmament of a world in which no human rightly belongs, at least not one whose flesh has been scoured under gas-heated water, who dons fabrics composed of meticulously complex fibers weekly cleansed in a chemically stewed machine vortex. Bats lurched and dived to snatch unseen prey, crowding the air with hectic, predatory pursuits which mirrored and amplified the groping chaotic alarm of Tom’s most desperately savage thoughts. Into July, he was becoming increasingly frazzled and gnawed at, beset from all sides by silent curses and unvoiced hatreds.

Then one Friday he saw Ashley at Henry’s with a group of people he didn’t know, a group which included no less than three men who each might’ve been the one who served as his replacement. They played polite, but Tom told the friends he’d arrived with he was feeling ill and excused himself. Walking back to his apartment, he felt his soul building up the volatile force to explode out of his body through a howling roar whose rippling shockwave would shatter every building and house for miles around him, wipe the slate of the earth clean of this taint permeating his existence down to each individual blood cell and neuron. Up the stairs and through his door, he collapsed to his hands and knees, sowing half-imaginary, half-planned destruction on every object his eyes lit upon: the couch that used to be hers, the picture she’d given him as a birthday gift, the old-fashioned TV she used to tease him about. The wooden shelf beside the door, where he dropped his keys and his wallet when returning home—the middle shelf he never used, with forgotten odds and ends, and the little green pouch his friend from the island of Hispaniola had given him as thanks.

***

“I don’t know if it was just the state I was in before I smoked it, or if the shit was laced with something,” Tom said. By the time he was taking the second of three hits, he knew he had to get outside. “I was queasy, claustrophobic. Every time I moved my eyes the light and colors would streak. I thought I should sit still and try not to move, but it was like my skin was on fire. Now it’s hard to remember what actually happened—I don’t remember leaving the house, or where I went at first. I remember turning onto Thieme and stepping into this alien world, this jungle hell that shouted back in flames at every shouting thought in my head. And I wanted to burn. I wanted to be flayed. I needed something to sever my mind from the fucking sinkhole it was trapped in—no matter where I went I was still back in Henry’s, in her apartment, in some guy’s apartment. No matter where I went Ashley was fucking some guy right in front of me.

“I smelled his cigarette before I saw him. He probably called me a faggot, but if he did I never heard it. I turned and saw him sitting there on that step. Though all I could really see was the orange light of his cigarette. I think I would’ve just walked past him if my eyes hadn’t locked on it, glowing, swaying, bouncing along with the words I never heard. I must’ve walked right up to him. Then he lunged, thrusting his face at me like he’d done before, trying to get me to flinch. Only I didn’t see his face. I saw something more like a bat’s face, something like an African tribal mask. I saw something with blue and red teeth like broken shards of stained glass trying to bite me, to devour me. I was so charged up with rage, and now with fear, and he was coming up from his sitting position. I came down with a right cross, my whole body twisting, all my weight. I probably smashed his jaw with that first punch. But what I saw was this bat’s face with the shards of stained glass for teeth still trying to bite my face off.

“I remember a lot of pulling and dragging. And I remember pummeling him in the middle of the street, bouncing his head off the pavement. I kept at it because I was sure somehow that I couldn’t really hurt him. I thought I heard him cackling even after his body had gone limp. It made me think it was all part of some trick he was playing on me—and it was infuriating. When my mind first started to clear, when I looked down and saw the guy—the walking barrel—with his face staved in, we were near the overlook. I knew he was dead. He had to be. But then I heard the fucking cackling again—and it scared the hell out of me. I dragged him to the bank and rolled him down, staying long enough to see his body come to rest at the base of the monument just on the edge of the retaining wall. And I ran.”

***

The lobelias were the last piece of the puzzle—or maybe the second to last. Tom had no faith in the law to expiate his sin. He needed to enact some form of penance, and he believed his demon-haunted dreams were guiding him toward it. “I drove my car over there in the middle of the afternoon, in broad fucking daylight. I figured the whole point was to sort of bring what I had done to light, so if someone saw me and called the police, well, so be it. I popped open the hatchback, took a breath, and went down the bank. I was still holding out the hope that I had hallucinated the whole thing. But there he was, rotting, covered in maggots and swirling flies. But you could still see what I’d done, how I’d smashed in his face. I’m afraid that I’ll be seeing that face every time I close my eyes until the day I die. And the smell… I can’t even look at meat anymore. The smell of fish makes me retch.”

Tom overmastered his repulsion, leaned down over the corpse, and returned to an upright position with it clasp to his chest, surprised by its lightness, by how much flesh had already rotted away. He hoisted one of the perfectly supple dead arms up and twisted under it. He gripped the wrist of the arm thus draped over his shoulder and began the trudge back up the bank. Midway into the climb, the body no longer seemed so light, and his recently mended rib began to prick again. Sweating, panting, wincing against the pain in his side and the stench of putrescence and shit, Tom crested the bank, paused for a breath, and continued toward the passenger side of his car—having decided against using the hatch. He fumbled with the door, and then made a ramp of his body down which the dead one slid into the passenger seat. After making some final adjustments, he belted in the proof of his crime—upright for anyone to see who cared to look.

Tom walked back to close the hatch, stood for a moment considering the gore spattered and smeared all over his clothes, and then went to the driver’s side door, got in, started the car, and drove away. No one saw him. He made the twenty-minute drive to the north side of town with the raw meat of the walking barrel’s face variously propped and bouncing against the window across from him, made the drive without incident. “I kept having to reach over and keep it from pitching forward, or from rolling over onto me. I thought for sure it was only a matter of time until I heard sirens. But I just kept driving, putting it in fate’s hands. The risk was part of the punishment I guess. Even when I pulled off to the side of the road to vomit, though, no one seemed to care much. I made it all the way to Union Chapel and into the tree-lined driveway without noticing anyone even looking at us funny.”

***

I met Tom the week after he’d buried the walking barrel’s body beside the cluster of blue lobelias at the head of the driveway to the old abandoned house on Union Chapel. I tried to work out the timeline. I’d met Marcus at Old Crown only days after Tom had moved the body. How the hell how had Marcus even known any of this was going on? Did Tom have a confidante, another confessor, a mutual acquaintance of Marcus’s? I had by now settled on a policy of giving Marcus the benefit of the doubt and proceeding with the project—at least until I had all the information and could tell for sure whether something was amiss. I wonder how many ongoing crimes throughout history have sustained themselves on just this type of moment-by-moment justification. I wrote Tom’s story as if it were completed, even though I had arranged another interview. I tried to heighten all the ghostly elements, considered suggesting the lobelias at the house had been seen glowing, maybe throw in some sightings of a spirit wandering around amid a cloud of flies, the face stove in. But the leap from fresh wound to fun game was difficult to make, reminding me that all ghost stories begin with personal tragedies.

Then the final interview: Tom has lost his job at EntSol; the Car-Ride of Horror has failed to quell his hallucinations; he’s seeing the bat-featured, tribal mask face with its mouth-full of broken stained glass hovering outside the windows of his apartment; and he’s returned to the house on Union Chapel at least once—to dig up the body he’d buried there, sling it over his shoulder again, and carry it down to the end of the drive and back as further penance. When he told me he took the knife that was still clipped inside the guy’s pocket and used it to carve and dismember the body before reburying it, I wasn’t sure I should believe him. It was too much. Or maybe I just didn’t want to believe it. I’d already written up the story and sent it as a PDF to Marcus, who in turn had sent it via email to the seven participants in the upcoming inaugural event. I told myself we could go through with it and concentrate on helping Tom once it was over.

Marcus had invited me to attend—or rather insisted that I do. He’d already sent me a check for the PDF.

***

From Tom’s description of the place, I’d imagined a desolate beige field with nothing but the pine tree borders marking off the old yard, but there was in fact a stand of aged trees in the back providing enough foliage to encircle the fire pit we constructed there. Marcus’s idea was to let everyone settle in and get cozy until it got dark, when we’d walk as a group up to the spot where the earth was disturbed (what an expression!) and the lobelias bloomed. Once we were all gathered there, I would tell the story, and then everyone would return to the safety and warmth of the fire. And it had all actually gone quite well—I was pleased with my somewhat improvised oral rendition of the tale—but I was getting nervous.

A few of the clients were already there when I arrived, and I hadn’t been afforded any opportunity to pull Marcus aside and put my questions to him. Then the two women I’d seen working the counter at his coffee shop showed up. They were introduced simply as helpers for some of the activities planned for later in the night, and they gave no indication of recognizing me. Still, I figured Marcus must know I’d been checking up on him. After the tale-telling, as we sat circling the fire, strange noises began coming from inside the old house. I confess, my nervousness had less to do with how Marcus might respond to my insubordination or the impropriety of profiting from the ongoing suffering of an imperiled man—and more to do with the likelihood that Marcus had arranged for some hokey theatrics to ensure a memorable experience for his clients so he could count on his precious word-of-mouth endorsements. What ever happened to not being cheap?

There ended up being six clients, two couples and a single of each gender, so with Marcus, me, and the two baristas, we made up a camp of ten, all crowded in a half-circle around the impressive fire Marcus had prudently prepared to keep well fueled long into the night. Now that the principle specter’s story had been rehearsed (hearse?), the ascendency of the walking barrel’s ghost established, I was turned to for more stories to, as it were, get the ball rolling. I told the one about the house in Garrett where men frequently see a gorgeous young woman standing in a second-story window, holding a candle and beckoning to them; as they stand there struck dumb by her spectral beauty, she transforms by imperceptible increments into first an old hag and then finally into an ashen-faced demon. Next, I extemporized a story about a group of boys from Carroll High School who made a game out of prowling through The Bicentennial Woods, a nature preserve up off Shoaff Road, waylaying hikers and ritualistically torturing them to death in the old farmhouse that still stands in the field behind the park; when one of the boys’ conscience got to him, he told a football player about the murders; the football player in turn stalked the killers and picked them off one by one—but of course they still haunt the woods and are thought to be behind occasional disappearances.